Impacts of Surveillance “Statecraft” in the Lakes Region — “Takings” of Personal Data

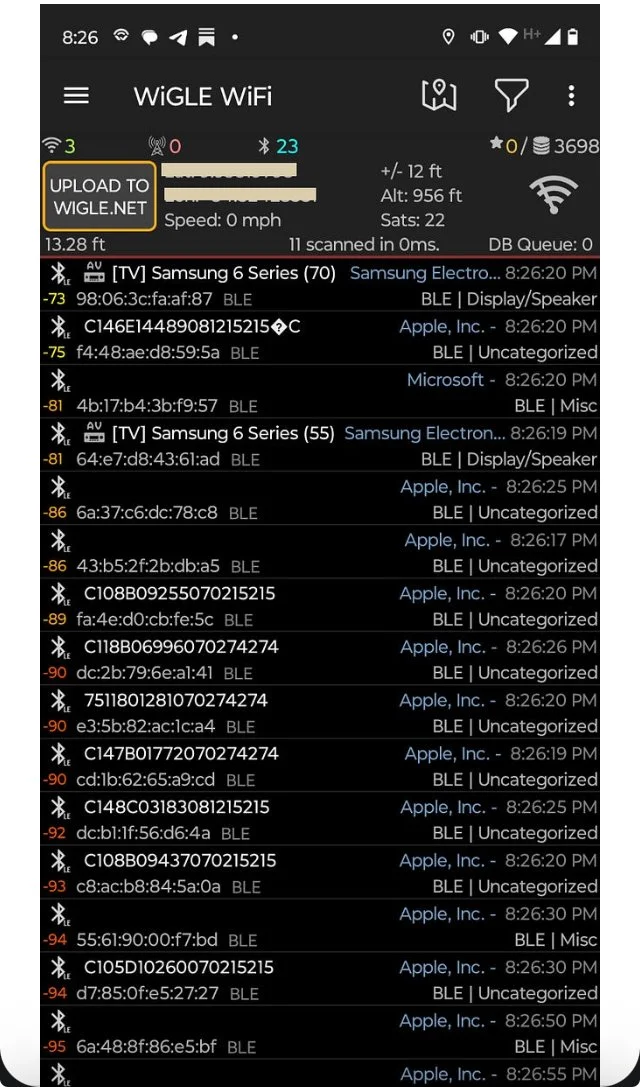

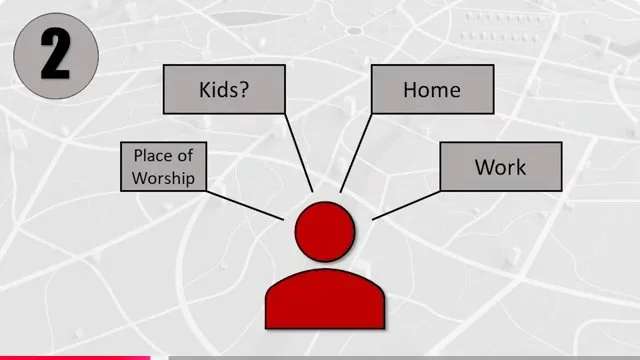

UPDATED 11.08.2025. This Blog Post is an updated edited version which includes text and video information on current DIGITAL geofence technologies using Location of device software; which is already in use in the Lakes Region. As well, a discussion on fixed cameras and drone camera surveillance in CURRENT USE is presented, encompassing nationwide programs; which began in widespread adoption 2015. The DATA being collected, and sold to third parties, without the knowledge or consent of those whose DATE is and has been collected cannot be overstated.

A hidden and emerging covert “Garrison State” (Howard Lasswell, 1941) “Panopticon” (Jeremy Bentham, 16th Century) is emerging into public view — Creating and Profiting from the covert “taking” and selling of personal DATA. Rights of Privacy are unknowingly usurped and abridged by unseen public-private partnerships selling personal DATA of Americans without their knowledge and consent. Yes! THIS DOES INCLUDE THE LAKES REGION.

Introduction | 1600’s Roots of 24/7 “Panopticon” Surveillance in America. The concept is far from a new method of control:

Topics addressed in this new blog post include:

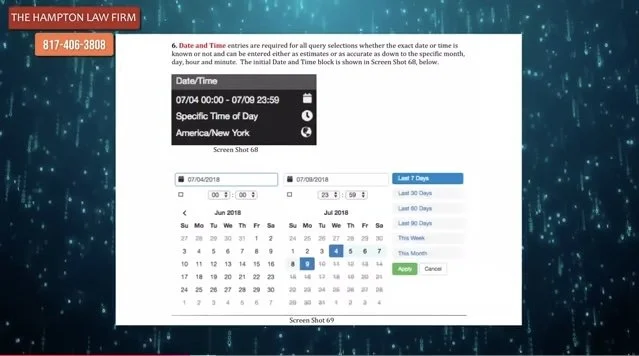

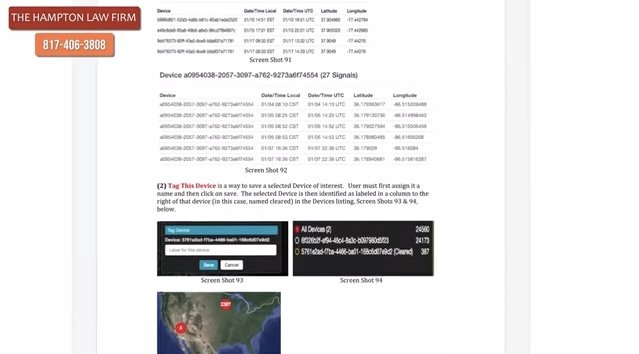

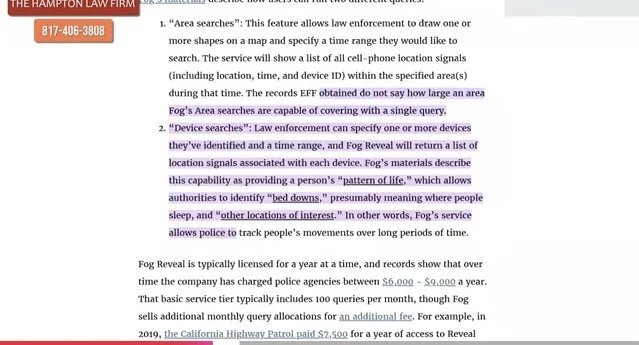

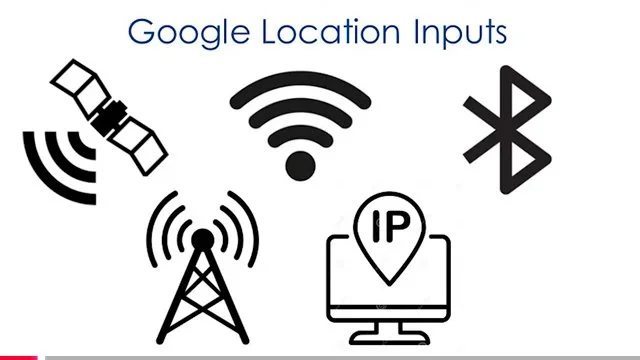

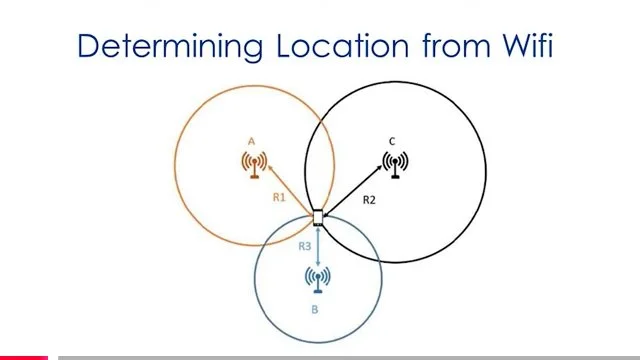

— the Surveillance state of human beings and their data in the context of current platforms being used right now nationwide, including geofencing and drone usage deploying “Fog Reveal” and Google Location (with third party apps) on most phones of the community in the Lakes Region;

— the fundamental Right of Privacy at home, in private affairs and to personal DATA;

— the long history of Surveillance since the 1600’s (Panopticon); the privatization and militarization of the Garrison state in America;

— soft power Statecraft management and funding of the foregoing; and

— violations of the Right to Privacy “Article 2-b” of the New Hampshire Constitution — in the form of “general warrants” deploying geofencing and drone usage surveillance for DATA CAPTURE.

Some may feel initially that the topic title may not be relevant to the Lakes Region community. Before making a snap decision about that, consider the importance of the recent Master Plan kickoff meeting which took place on October 6, 2025 — and which promises to provide a 15-20 year land use plan for Laconia. As well, Laconia is currently considering “social districts” reported from news outlets recently. Often such plans in other communities and districts have included camera and other surveillance installations such as streetlight and road way “furniture” including sensors and cameras embedded in street lights and tethered and untethered drones discussed below.

This blog post addresses the 400 year history of surveillance systems of human beings, their underlying premises and justifications, and the meteoric growth of surveillance today throughout America.

Surveillance and data collection is now a massive industry; and it represents a potentially new revenue center for collection and sale of personal, private DATA by both businesses, and municipalities.

While keeping an open mind, it is not unreasonable to assume “surveillance” will be one of many topics for regional and local municipal districts’ planning discussions, whether public or not. Certainly public safety is always a high priority in such master plan discussions; which has in other communities tended to be emphasized unfairly over related and important questions —such as — who profits? and how is the fundamental Right of Privacy honored as well as ownership of private DATA?

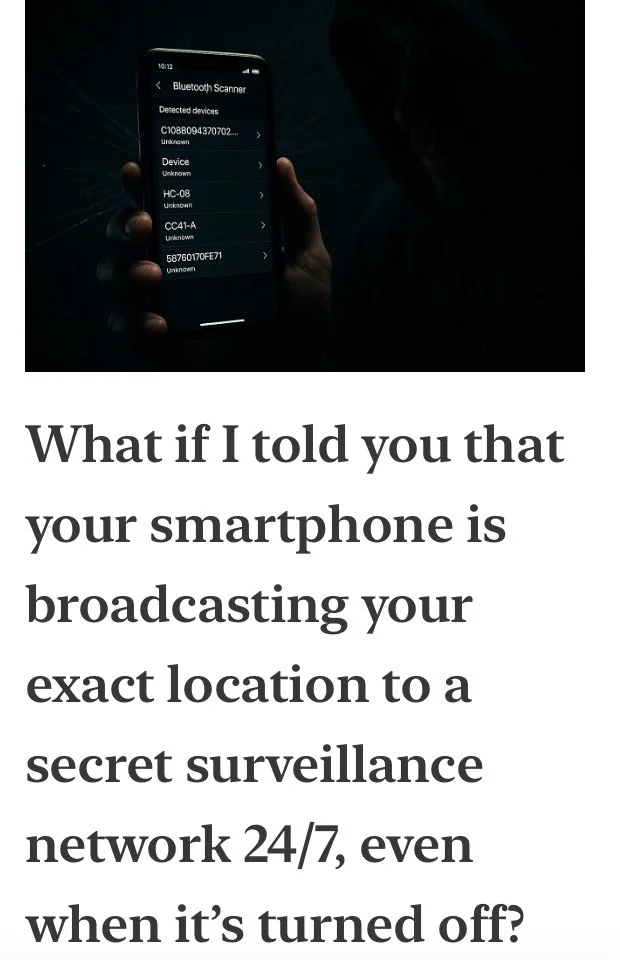

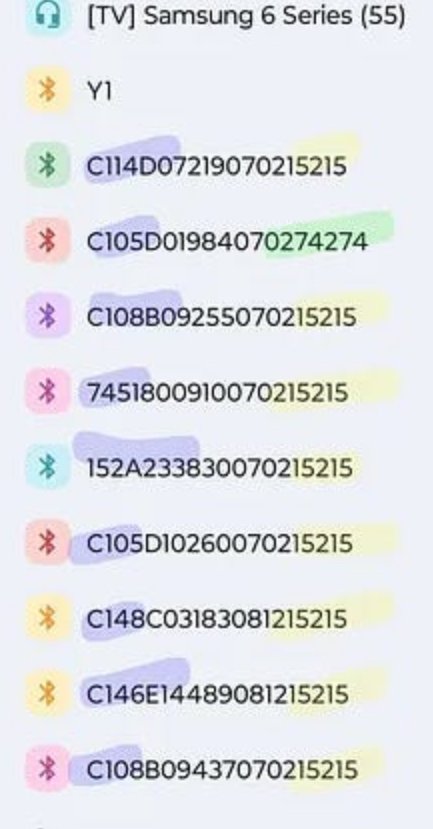

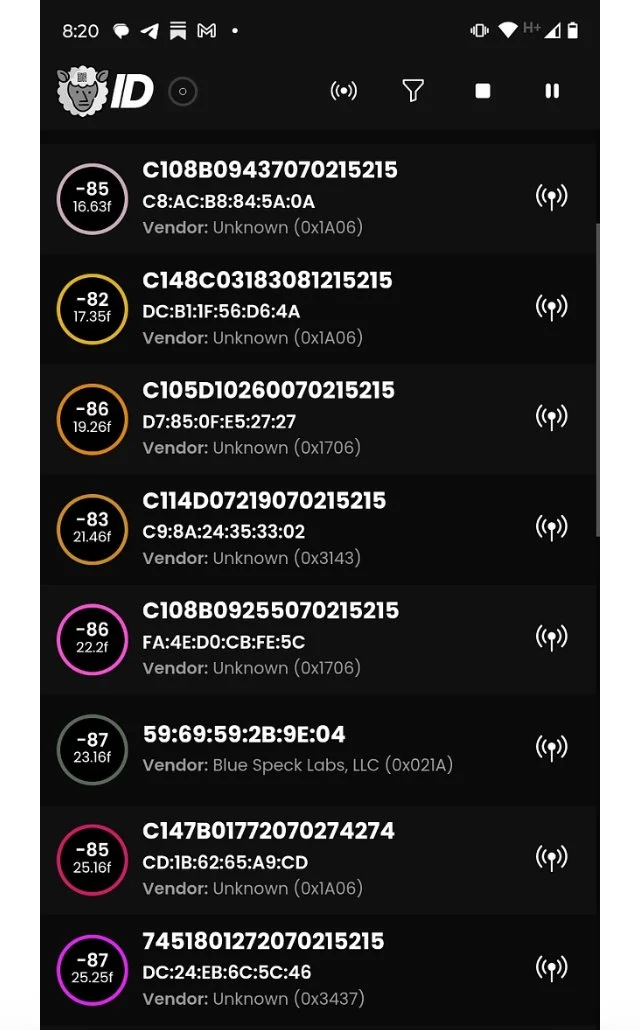

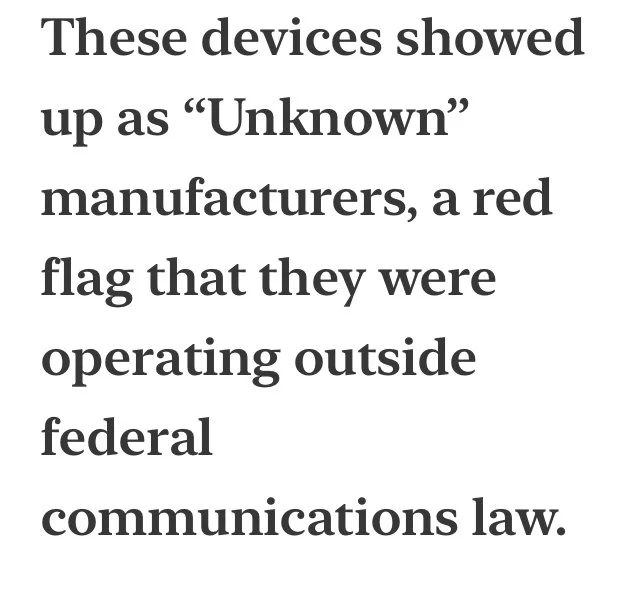

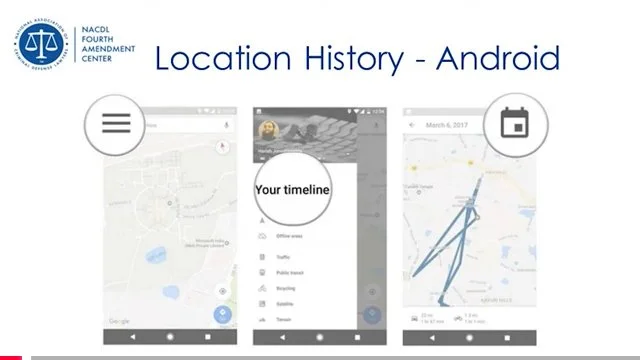

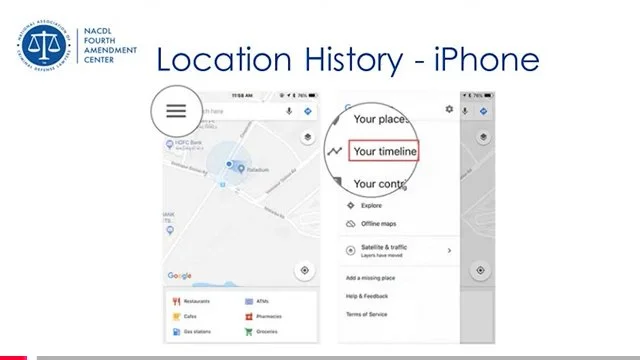

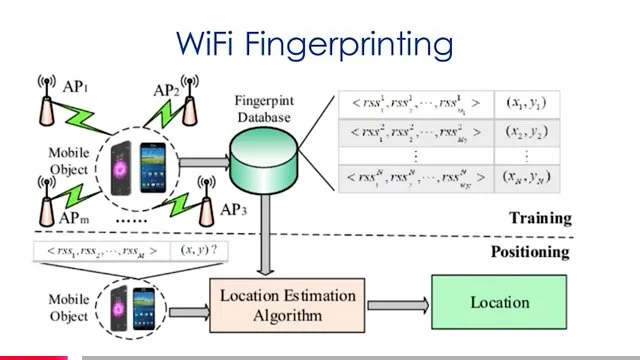

Let’s Start with Current Smartphone Capabilities and Bluetooth Data Transmissions

Several Typical Reactions and Opinions of Americans to Covert Surveillance include:

— Nothing to hide — so why should I — OR YOU — be concerned?

— They cannot do that … or can THEY?

— THEY need probable cause and a search warrant to surveil me and to take my personal picture, record my voice, scrape my device (phone, laptop) data — RIGHT?

— They already have my information and data, so what’s the problem with them having more?

— “Publicly” operated traffic and street cameras (on light poles or in the lighting fixture itself) recording visual and audio for traffic, pedestrian facial recognition (with lip reading capacities) on:

• sidewalks,

• parking lots,

• hospitals,

• parks,

• libraries,

• public and private buildings,

• events,

• rallies,

• protests,

One Example of Why this Blog Post on Surveillance Is Relevant to the Lakes Region Cities/Towns and Community Members - Tethered Drones and Cameras with Software

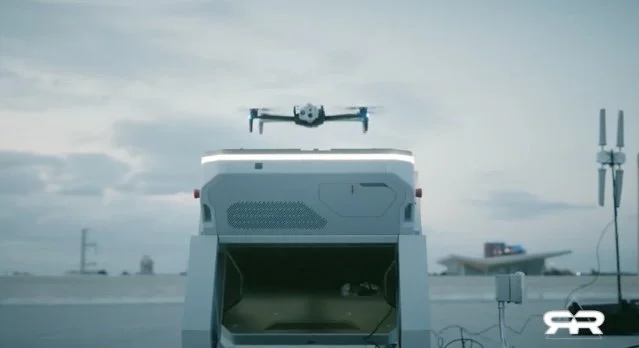

The following represent Requests for Proposal bids were issued within the last year for tethered drones without any real specificity as to the camera and onboard sensor specs (i.e., collection of personal private DATA including cell phone IDs and locations, facial recognition, license plate readers, etc.) and DATA sharing/management software installed on the drones and/or remote sites connected to them. The cost of the drones is specified as $133,542 for the first year; and the beginning is uncertain. Apparently these initial funds are to be provided by a Homeland Security grant. The source of the slides below is the City of Laconia — with a query submitted of “surveillance” and “drones”.

Because of the extensive subject matter of this blog post, there is no human way to adequately cover the ground touched upon below. Space limitations prevent that. And this is particularly true when it comes to Facial Recognition technology, software and its known, disclosed and undisclosed, deployments in communities across America by: (1) municipalities, (2) commercial establishments, such as box stores, and (3) our own electronic devices such as personal, private picture collections saved on our devices and used in Facial Recognition databases.

Consequently a follow-up blog post is forthcoming entitled “Facial Recognition — Surveillance in the Lakes - What are the REAL Consequences?”

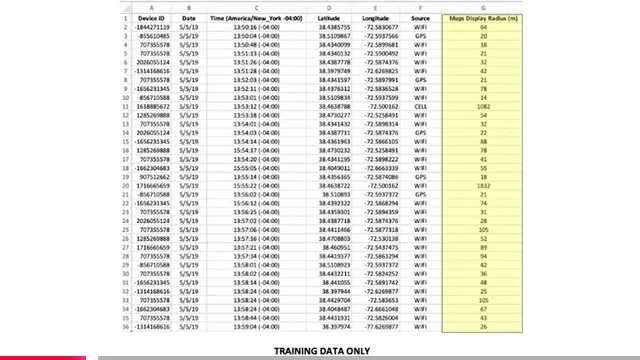

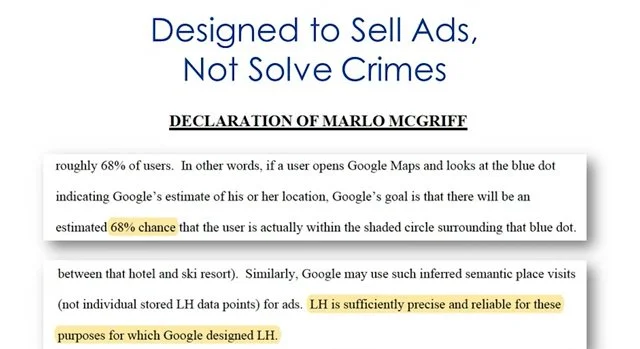

Let’s Next Look At Two Current Current Surveillance Platforms in Use Nationwide

Fog Reveal | Google Location App (Networked with Third Party Apps)

SEE: The text of the US vs. Smith Decision Referred to Above.

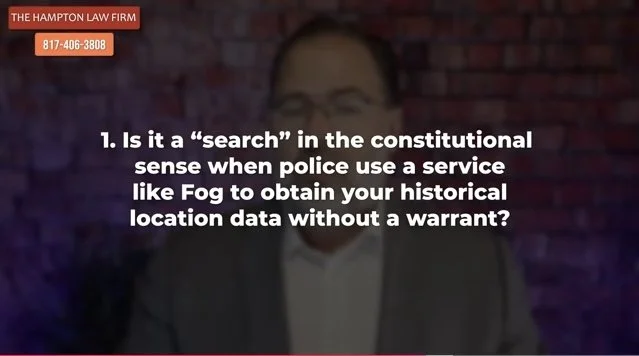

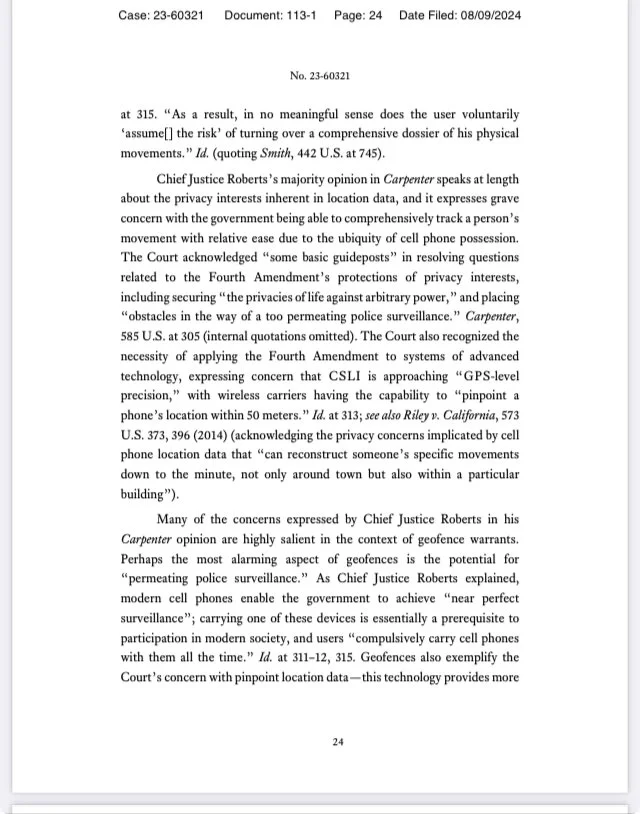

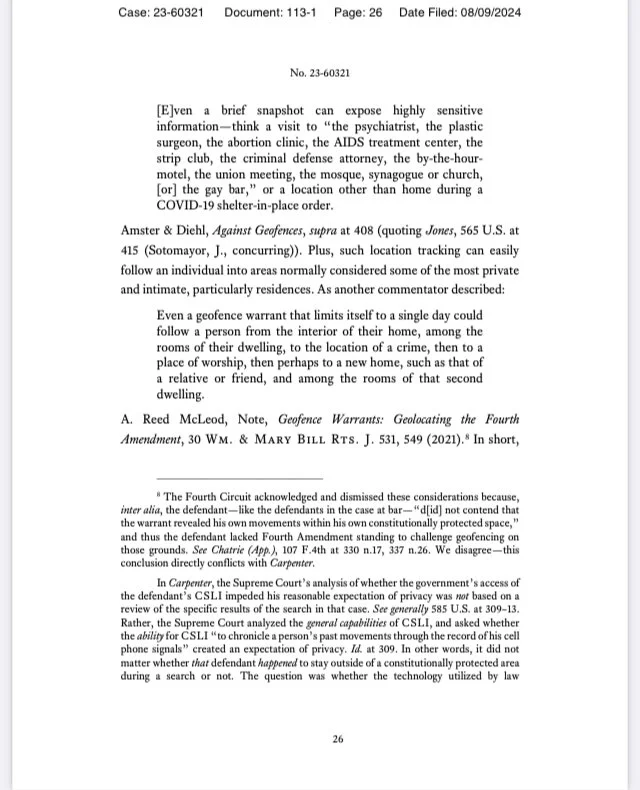

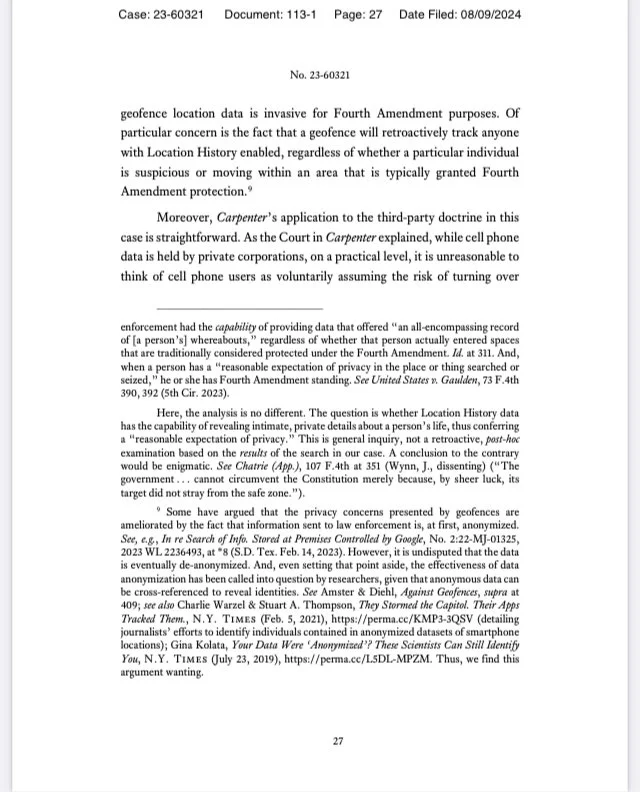

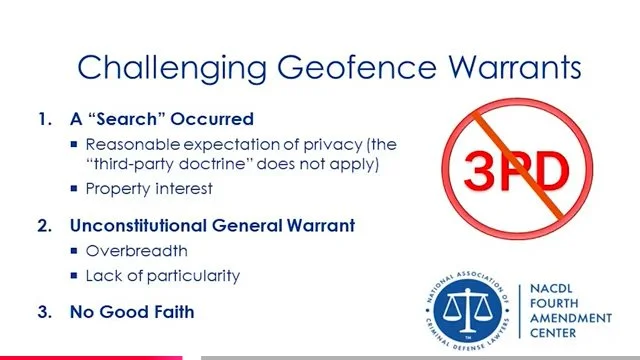

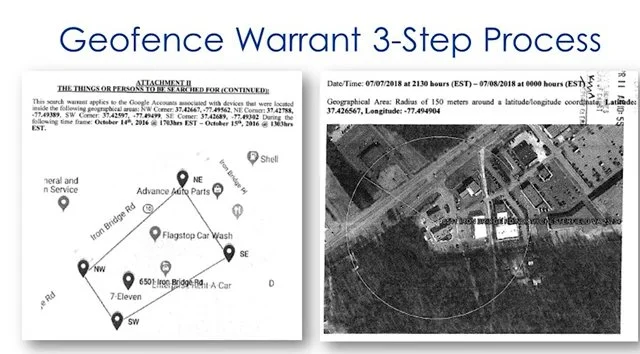

THE CIRCUIT COURTS ARE NOW SPLIT ON THE ISSUE OF GEOFENCING SURVEILLANCE WARRANTS. On August 9, 2024, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in United States v. Smith that geofence warrants are unconstitutional under the Fourth Amendment as modern-day general warrants. See U.S v. Smith, 110 F.4th 817 (5th Cir. 2024). The opinion directly conflicts with the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals’ recent decision in U.S. v. Chatrie, 107 F.4th 319 (4th Cir. 2024).

NOTABLY, at the time Mississippi did not have any form of personal right to privacy contained within its state Constitution nor its state statutes. UNLIKE Mississippi, New Hampshire does have such a right to privacy of personal information AND IT IS SPECIFIED AS INHERENT, NATURAL AND ESSENTIAL.

[Art.] 2-b. [Right of Privacy.] An individual's right to live free from governmental intrusion in private or personal information is natural, essential, and inherent. Enacted December 5, 2018

Were the Smith case, or facts similar to it, brought in New Hampshire, Article 2-b might be an additional and stronger fundamental rights (i.e., inherent, unalienable) foundation; in addition to, a “takings” (abrogation claim) of fundamental “property rights” described in other Articles of the New Hampshire Constitution and relevant case law.

The Concurring Opinion of the Court in Smith provides the following insight on its decision in Mississippi:

James C. Ho, Circuit Judge, concurring:

Geofence warrants are powerful tools for investigating and deterring crime. The defendants here engaged in a violent robbery—and likely would have gotten away with it, but for this new technology. So I fully recognize that our panel decision today will inevitably hamper legitimate law enforcement interests.

But hamstringing the government is the whole point of our Constitution. Our Founders recognized that the government will not always be comprised of publicly-spirited officers—and that even good faith actors can be overcome by the zealous pursuit of legitimate public interests. “If men were angels, no government would be necessary.” The Federalist No. 51, at 349 (J. Cooke ed. 1961). “If angels were to government, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.” Id. But “experience has taught mankind the necessity of auxiliary precautions.” Id. It’s because of “human nature” that it’s “necessary to control the abuses of government.” Id.

Our decision today is not costless. But our rights are priceless. Reasonable minds can differ, of course, over the proper balance to strike between public interests and individual rights. Time and again, modern technology has proven to be a blessing as well as a curse. Our panel decision today endeavors to apply our Founding charter to the realities of modern technology, consistent with governing precedent. I concur in that decision.

See also Brian L. Owsley, The Best Offense Is a Good Defense: Fourth Amendment

Implications of Geofence Warrants, 50 Hofstra L. Rev. 829, 834 (2022). This law review article is quoted extensively by the the Court in its decision excerpted below in the slideshow carousel.

A Deeper Dive on Surveillance and Geofencing — as a Search without a Warrant — And The Issue of Geofencing Being a “General Warrant” Proscribed by the National Constitution AND state Constitutions Like New Hampshire Article 2-b

What we are really discussing here are the capabilities of technologies incolving cameras and DATA collection of personal, private information - its collections without a warrant supported by probable cause - and its sale to third parties without the owners of that DATA’s knowledge or meaningful consent. Is this really significant in the Lakes Region? Yes it is - as well as nationwide.

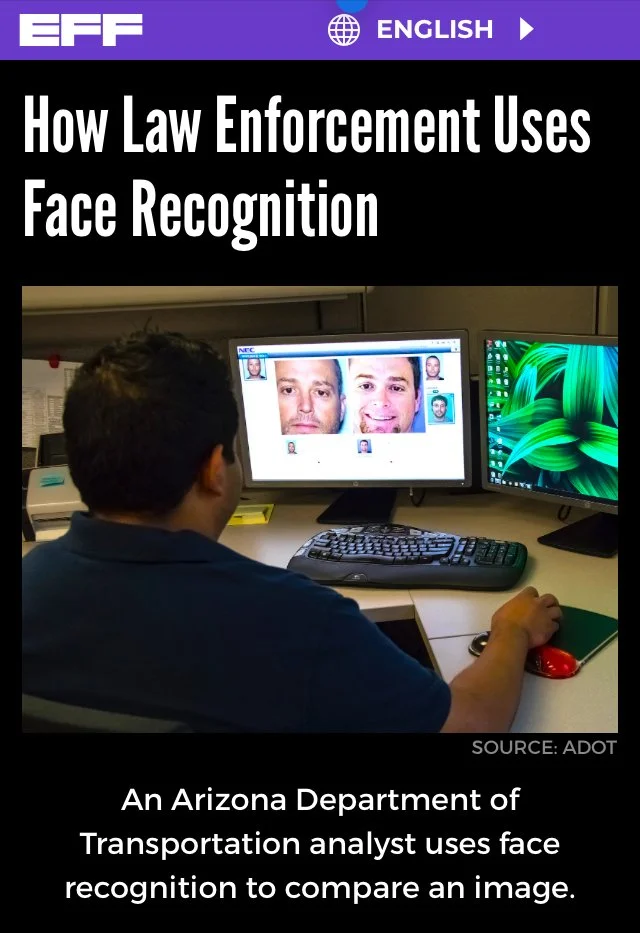

The following slide carousel is sourced from the Electronic Frontier Foundation EFF. In the slides, the Arizona Department of Transportation is using FR technology. One can only speculate why and whether people traveling in vehicles are aware the surveillance is actually taking place and whether a warrant with probable cause preceded the scan. Also the Police Department is scanning a face in San Diego. Again, the question is here whether the officer scanning had probable cause of a crime — they personally witnessed taking place; that is, BEFORE the scan was initiated, AND whether the person being scanned was under arrest AND HAD BEEN READ THEIR MIRANDA RIGHTS.

Let’s Consider This One of Many Examples — Surveillance Cameras — with Facial Recognition Capabilities.

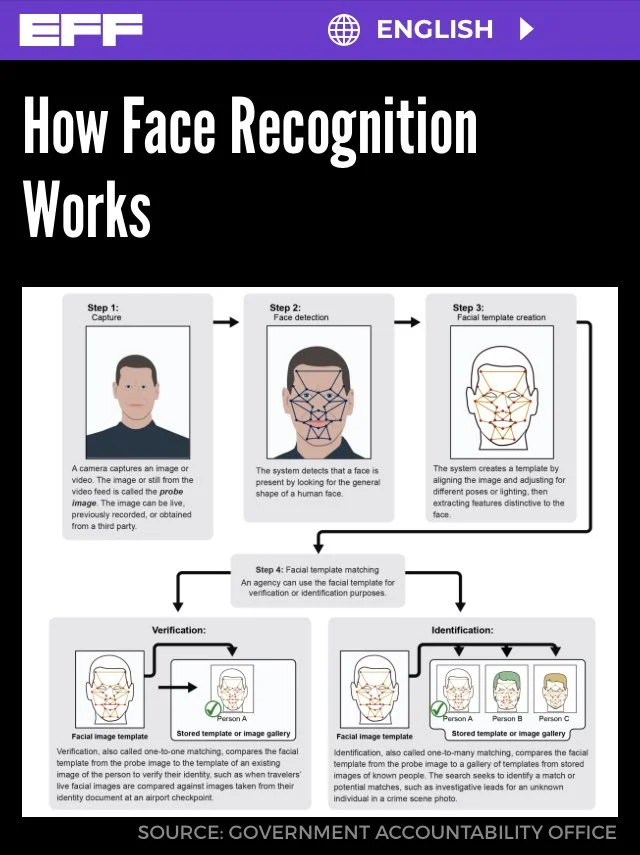

Face recognition is a biometric technology that uses a face or the image of a face to identify or verify the identity of an individual in photos, video, or in real-time. It is commonly used by law enforcement and private businesses. Face recognition systems depend on databases of individuals’ images to train their underlying algorithms. Face recognition can be applied retroactively to video footage and photographs, it can be used in coordination with other surveillance technologies and databases when creating profiles of individuals, including those who may never have been involved in a crime. It can facilitate the tracking of individuals across video feeds and can be integrated into camera systems and other technologies, as we have seen at sporting events in the United States.

Face recognition can be prone to failures in its design and in its use, which can implicate people for crimes they haven’t committed and make people into targets of unwarranted or dangerous retaliation. Facial recognition software is particularly bad at recognizing Black people and other ethnic minorities, women, young people, and transgender and nonbinary individuals. People in these demographic groups are especially at risk of being misidentified by this technology and are disparately impacted by its use. Face recognition contributes to the mass surveillance of individuals, neighborhoods, and populations that have historically been targeted by unfair policing practices, and it has been used to target people engaging in protected speech and alienate perceived enemies.

Hundreds of law enforcement agencies and a rapidly growing number of private entities use face recognition across the United States. Its use in other countries is also growing. Face recognition generally falls into two categories: face verification and face identification. Face recognition systems use computer algorithms to pick out specific, distinctive details about a person’s face and make a judgment of its similarity to other faces. Details, such as distance between the eyes or shape of the chin, are converted into a mathematical representation and compared to data on other faces collected in a face recognition database. The data about a particular face is often called a face template and is distinct from a photograph because it’s designed to only include certain details that can be used to distinguish one face from another. The term “face recognition” is also often used to describe “face detection” (identifying whether an image contains a face at all) and “face analysis” (the assessment of certain traits, like skin color and age, based on the image of a face). Face verification typically compares the image of a known individual against an image of, ideally, that individual, to confirm that both images represent the same person.

Face identification generally involves comparing a sample image of an unknown individual against a collection of known faces and attempting to find a match. Some face recognition systems, instead of positively identifying an unknown person, are designed to calculate a probability match score between the unknown person and specific face templates stored in the database. These systems will offer up several potential matches, ranked in order of likelihood of correct identification, instead of just returning a single result. Face recognition systems vary in their ability to identify people under challenging conditions such as poor lighting, low quality image resolution, and suboptimal angle of view (such as in a photograph taken from above looking down on an unknown person).When it comes to errors, there are two key concepts to understand: A “false negative” is when the face recognition system fails to match a person’s face to an image that is, in fact, contained in a database. In other words, the system will erroneously return zero results in response to a query. A “false positive” is when the face recognition system does match a person’s face to an image in a database, but that match is actually incorrect. This is when a police officer submits an image of “Joe,” but the system erroneously tells the officer that the photo is of “Jack.” When researching a face recognition system, it is important to look closely at the “false positive” rate and the “false negative” rate, since there is almost always a trade-off. For example, if you are using face recognition to unlock your phone, it is better if the system fails to identify you a few times (false negative) than it is for the system to misidentify other people as you and permit those people to unlock your phone (false positive). If the result of a misidentification is that an innocent person goes to jail (like a misidentification in a mugshot database), then the system should be designed to have as few false positives as possible.

Many local police agencies, state law enforcement, and federal agencies use face recognition in routine patrolling and policing. Scores of databases facilitate face recognition use at the local, state and federal level. Law enforcement may have access to face recognition systems through private platforms or through systems designed internally or by other government agencies. Law enforcement can query these vast databases to identify people in photos taken from social media, closed-circuit television (CCTV), traffic cameras, or even photographs they’ve taken themselves in the field. Faces may also be compared in real-time against “hot lists” of people suspected of illegal activity. Federal law enforcement agencies, like the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the State Department, contribute to research and development, and many other agencies have stated their intentions to expand their use of face recognition.

Police agencies may use face recognition to try to identify suspects in a variety of crimes. While police often will assert that face recognition will help them to locate people who have committed violent crimes, there have been multiple instances in which the technology has been used in investigations of much lower-level offenses.

Following the murder of George Floyd in 2020 and the resulting protests and civil unrest, federal agencies used face recognition to identify individuals. Three agencies have also admitted using the technology to identify individuals present at the January 6, 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol.

The use of face recognition by federal law enforcement agencies is widespread. Agencies use face recognition to generate investigative leads, access devices, and get authorization to enter particular physical locations. At least 20 of 42 federal agencies with policing powers have their own or use another government agency’s face recognition system, according to a July 2021 report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO). Agencies reported accessing one or more of 27 different federal face recognition databases.

Face recognition systems in 29 states are accessed and used by federal law enforcement agencies; the extent of this use is not fully known, as at least 10 of the federal agencies accessing these systems do not track use of non-federal face recognition technology, despite GAO recommendations that they do so.

Law enforcement is increasingly using face recognition to verify the identities of individuals crossing the border or flying through U.S. airports. The Transportation Security Administration (TSA) is integrating face recognition into many of the country’s airports. As of early 2023, TSA had introduced the technology to 16 major airports, and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) had implemented face recognition technology. at 32 airports for passengers leaving and entering the United States.

Some face recognition systems are based on the mugshots of individuals. Police collect mugshots from arrestees and compare them against local, state, and federal face recognition databases. Once an arrestee’s photo has been taken, the mugshot will live on in one or more databases to be scanned every time the police do another criminal search.

The FBI’s Next Generation Identification database contains more than 30 million face recognition records. FBI allows state and local agencies “lights out” access to this database, which means no human at the federal level checks up on the individual searches. In turn, states allow FBI access to their own criminal face recognition databases.

FBI also has a team of employees dedicated just to face recognition searches called Facial Analysis, Comparison and Evaluation (“FACE”) Services. FACE can access more than 400 million non-criminal photos from state Departments of Motor Vehicles (DMV) and the State Department; at least 16 U.S. states allow FACE access to driver’s license and ID photos. As of 2019, the FBI had conducted nearly 400 thousand searches through FACE services.

Estimates indicate that over a quarter, at least, of all state and local law enforcement agencies in the U.S. can run face recognition searches on their own databases or those of another agency. As of September 2023, the EFF’s Atlas of Surveillance, the largest database of known uses of surveillance technology by law enforcement, had cataloged nearly 900 municipal, county, and state agencies using face recognition.

Face recognition doesn’t require elaborate control centers or fancy computers. Mobile face recognition allows officers to use smartphones, tablets, or other portable devices to take a photo of a driver or pedestrian in the field and immediately compare that photo against one or more face recognition databases to attempt an identification.

More than half of all adults in the United States have their likeness in at least one face recognition database, according to research from Georgetown University. This is at least partially due to the widespread integration of DMV photographs and databases. At least 43 states have used face recognition software with their DMV databases to detect fraud, and at least 26 of states allow law enforcement to search or request searches of driver license databases, according to a 2013 Washington Post report; it is likely this number has since increased.

Local police also have access to privately-created face recognition platforms, in addition to federal systems. These may be developed internally, but increasingly, access is purchased through subscriptions to private platforms, and many police departments spend a portion of their budgets on access to face recognition platforms.

The Pinellas County Sheriff’s Office in Florida, for example, maintains one of the largest local face analysis databases. As of June 2022, its database contains more than 38 million images and was accessible by 263 different agencies.

Face recognition may also be used in private spaces like stores and sports stadiums, but different rules may apply to private sector face recognition.

Who Sells Face Recognition

Law enforcement agencies once attempted to create and share their own facial recognition systems. Now there are many companies that sell face recognition products to identify and analyze individuals’ faces at much lower costs than internal development.

Clearview AI is one such popular platform commonly used by law enforcement. Its database of more than 30 million photos, which is based on images scraped from a variety of online and public locations, is one of the most extensive known to be used.

MorphoTrust, a subsidiary of Idemia (formerly known as OT-Morpho or Safran), is another large vendors of face recognition and other biometric identification technology in the United States. It has designed systems for state DMVs, federal and state law enforcement agencies, border control and airports (including TSA PreCheck), and the state department.

Other common vendors include 3M, Cognitec, DataWorks Plus, Dynamic Imaging Systems, FaceFirst, and NEC Global.

Threats Posed By Face Recognition

Face recognition poses threats to individual privacy and civil liberties and can be used in coordination with other technologies in ways that are additionally threatening to individual rights and legal protections.

Face recognition data is easy for law enforcement to collect and hard for members of the public to avoid. Faces are in public all of the time, but unlike passwords, people can’t easily change their faces. Law enforcement agencies are increasingly sharing information with other agencies and across jurisdictions. Cameras are getting more powerful and more ubiquitous. More photographs and video are being stored and shared for future analysis. It is very common for images captured by a particular agency or for a specific purpose to be used in a face recognition system.

Face recognition data remains prone to error, even as face recognition improves, and one of the greatest risks of face recognition use is the risk of misidentification. At least six individuals have been misidentified by face recognition and arrested for crimes that they did not commit: Robert Williams, Michael Oliver, Nijeer Parks, Randal Reid, Alonzo Sawyer, and Porcha Woodruff. Being misidentified by face recognition can result in unwarranted jail time, criminal records, expenses, trauma, and reputational harm.

The FBI admitted in its privacy impact assessment that its system “may not be sufficiently reliable to accurately locate other photos of the same identity, resulting in an increased percentage of misidentifications.” Although the FBI purports its system can find the true candidate in the top 50 profiles 85% of the time, that’s only the case when the true candidate exists in the gallery. If the candidate is not in the gallery, it is quite possible the system will still produce one or more potential matches, creating false positive results. These people—who aren’t the candidate—could then become suspects for crimes they didn’t commit. An inaccurate system like this shifts the traditional burden of proof away from the government and forces people to try to prove their innocence. Face recognition gets worse as the number of people in the database increases. This is because so many people in the world look alike. As the likelihood of similar faces increases, matching accuracy decreases.

Face recognition systems are particularly bad at identifying Black, Brown, Asian, and non-gender conforming individuals. Face recognition software also misidentifies other ethnic minorities, young people, and women at higher rates. Criminal databases include a disproportionate number of African Americans, Latinos, and immigrants, due in part to racially-biased police practices; the use of face recognition technology has a disparate impact on people of color. Even if a company or other provider of a face recognition algorithm updates its system to be more accurate, this does not always mean that law enforcement agencies using that particular system discontinue use of the original, flawed system.

Individual privacy and autonomy of all people are threatened by the reach of constant tracking and identification. Face recognition data is often derived from publicly-available photos, social media, and mugshot images, which are taken upon arrest, before a judge ever has a chance to determine guilt or innocence. Mugshot photos are often never removed from the database, even if the arrestee has never had charges brought against them.

Face recognition can be used to target people engaging in protected speech. For example, during protests surrounding the death of Freddie Gray, the Baltimore Police Department ran social media photos through face recognition to identify protesters and arrest them. Of the 52 agencies analyzed in a report by Georgetown Center on Privacy and Technology, only one agency, the Ohio Bureau of Criminal Investigation, has a face recognition policy expressly prohibiting the use of the technology to track individuals engaged in protected free speech.

Face recognition may also be abused by individual officers or used for reasons unrelated to investigations or their work. Few face recognition systems are audited for misuse. Less than 10 percent of agencies admitting to face recognition use in the Georgetown survey had a publicly-available use policy. Only two agencies, the San Francisco Police Department and the Seattle region’s South Sound 911, restrict the purchase of technology to those that meet certain accuracy thresholds. Only one—Michigan State Police—provides documentation of its audit process.

There are few measures in place to protect everyday Americans from the misuse of face recognition technology. In general, agencies do not require warrants. Many do not even require law enforcement to suspect someone of committing a crime before using face recognition to identify them. While the Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act requires notice and consent before the private use of face recognition tech, this only applies to companies and not to law enforcement agencies.

Some argue that human backup identification (a person who verifies the computer’s identification) can counteract false positives. However, research shows that, if people lack specialized training, they make the wrong decisions about whether a candidate photo is a match about half the time. Unfortunately, few systems have specialized personnel review and narrow down potential matches.

Some cities have implemented bans on the use of face recognition. However, these bans and restrictions are constantly being undermined and adjusted at the behest of law enforcement. Virginia, for example, enacted a complete ban on police use of face recognition in 2021, only to roll back those restrictions the following year. In California, a three-year moratorium on face recognition passed in 2019, but the restrictions it implemented have not been reinstated since the temporary ban expired at the beginning of 2023. New Orleans replaced its 2020 ban with regulated access for the local police department. As face recognition databases expand their reach and law enforcement agencies push to use them, the threats posed by the technology persist.

EFF's Work on Face Recognition

EFF supports meaningful restrictions on face recognition use both by government and private companies, including total bans on the use of the technology. We believe that face recognition in all of its forms, including face scanning and real-time tracking, pose threats to civil liberties and individual privacy.

We have called on the federal government to ban the use of face recognition by federal agencies. We have testified about face recognition technology before the Senate Subcommittee on Privacy, Technology, and the Law, as well as the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform Hearing on Law Enforcement’s Use of Facial Recognition Technology. We also participated in the NTIA face recognition multistakeholder process but walked out, along with other NGOs, when companies couldn’t commit to meaningful restrictions on face recognition use. EFF has supported local and state bans on facial recognition and opposes efforts to expand its use. In New Jersey, EFF, along with Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) and the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL), filed an amicus brief supporting a defendant's discovery rights to know the face recognition algorithms used in their case, and the court agreed, a win for due process protections.

EFF has consistently filed public records requests to obtain previously secret information on face recognition systems. We’ve pushed back when cities haven’t properly complied with our requests, and we even sued the FBI for access to its face recognition records. In 2015, EFF and MuckRock launched a crowdsourcing campaign to request information on various mobile biometric technologies acquired by law enforcement around the country. We filed an amicus brief, along with the ACLU of Minnesota, demanding the release of emails regarding the Hennepin County Sheriff Office’s face recognition program that were requested by one local participant in the project.

EFF has repeatedly sounded the alarm on face recognition and work to educate the public about the harms of facial recognition, including through initiatives like our “Who Has Your Face” project, which helps individuals learn about the databases in which their image likely exists. EFF has supported local bans on face recognition and provides resources to activists who are fighting face surveillance.

EFF Legal Cases

EFF v. U.S. Department of Justice

Tony Webster v. Hennepin County and Hennepin County Sheriff's Office

Suggested Additional Reading

Garbage In, Garbage Out (Georgetown Law, Cennter on Privacy and Technology)

Face Off: Law Enforcement Use of Face Recognition Technology (EFF)

The Perpetual Line-Up (Georgetown Law Center on Privacy and Technology)

Federal Agencies’ Use and Related Privacy Protections (Government Accountability Office)

California Cops Are Using These Biometric Gadgets in the Field (EFF)

Face Recognition Performance Role of Demographic Information (IEEE)

SEE BELOW several books available from the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers NACDL for both criminal defense lawyers and laypeople interested in these topics LINK:

What About Other States? Are All States Handling Surveillance in the Same Manner? NO!

Montana Becomes First State to Close the Law Enforcement Data Broker Loophole DEEPLINKS BLOG BY MATTHEW GUARIGLIA, MAY 14, 2025

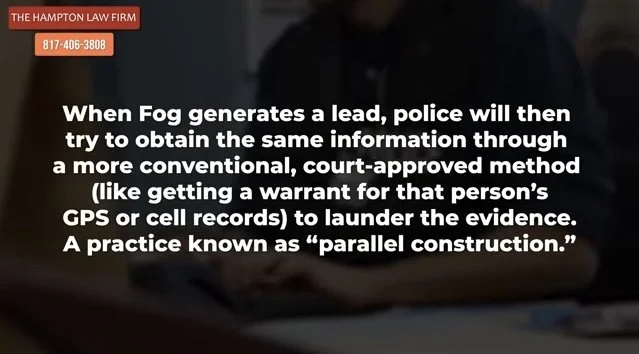

SOURCE: What does that mean? In every state other than Montana, if police want to know where you have been, rather than presenting evidence and sending a warrant signed by a judge to a company like Verizon or Google to get your geolocation data for a particular set of time, they only need to buy that same data from data brokers. In other words, all the location data apps on your phone collect —sometimes recording your exact location every few minutes—is just sitting for sale on the open market. And police routinely take that as an opportunity to skirt your Fourth Amendment rights.

Now, with SB 282, Montana has become the first state to close the data broker loophole. This means the government may not use money to get access to information about electronic communications (presumably metadata), the contents of electronic communications, contents of communications sent by a tracking devices, digital information on electronic funds transfers, pseudonymous information, or “sensitive data”, which is defined in Montana as information about a person’s private life, personal associations, religious affiliation, health status, citizen status, biometric data, and precise geolocation. This does not mean information is now fully off limits to police. There are other ways for law enforcement in Montana to gain access to sensitive information: they can get a warrant signed by a judge, they can get consent of the owner to search a digital device, they can get an “investigative subpoena” which unfortunately requires far less justification than an actual warrant.

Despite the state’s insistence on honoring lower-threshold subpoena usage, SB 282 is not the first time Montana has been ahead of the curve when it comes to passing privacy-protecting legislation. For the better part of a decade, the Big Sky State has seriously limited the use of face recognition, passed consumer privacy protections, added an amendment to their constitution recognizing digital data as something protected from unwarranted searches and seizures, and passed a landmark lawprotecting against the disclosure or collection of genetic information and DNA.

SB 282 is similar in approach to H.R.4639, a federal bill the EFF has endorsed, introduced by Senator Ron Wyden, called the Fourth Amendment is Not for Sale Act. H.R.4639 passed through the House in April 2024 but has not been taken up by the Senate.

Absent the United States Congress being able to pass important privacy protections into law, states, cities, and towns have taken it upon themselves to pass legislation their residents sorely need in order to protect their civil liberties. Montana, with a population of just over one million people, is showing other states how it’s done. EFF applauds Montana for being the first state to close the data broker loophole and show the country that the Fourth Amendment is not for sale.

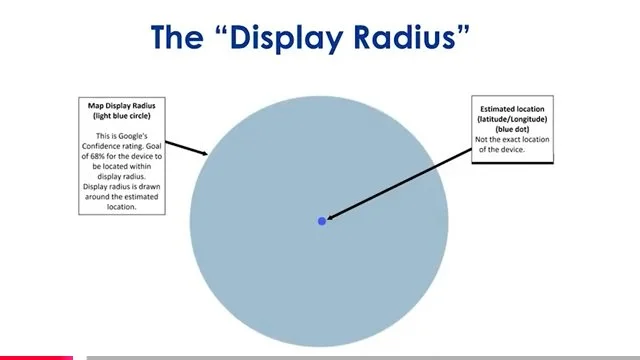

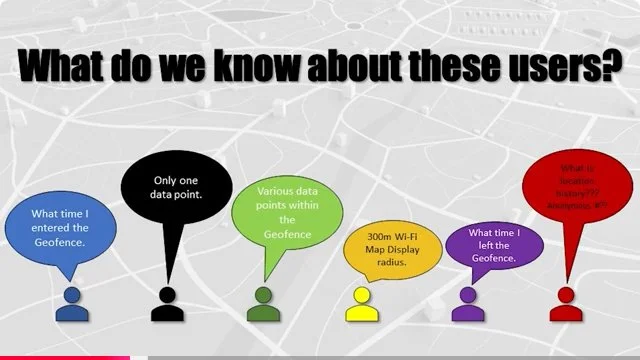

The following is a more lengthy video which covers all of the foregoing and is presented by a panel of three lawyers who were involved in many recent cases concerning geofencing, surveillance without warrants, the third party doctrine, good faith, and property rights takings. These lawyers were chosen as presenters to an audience of criminal defense lawyers as a yearly continuing legal education requirement lawyers have to complete. It is presented with many easy to understand slides and charts, where even a layperson Critical Thinking can understand the issues. A carousel of selections from those slides appears beneath the video. It is NOT ALL OF THEM for reasons of space limitations. Readers are encouraged to watch the entire video all the way through as there is far more information revealed concerning recent and current history of challenges to geofencing whether deployed through Google, Fog Reveal or other software platforms.

Surveillance Disguised as a Commercial Ad Platform for Marketers and Collection of Your Personal DATA — Offered for Sale

SOURCE: “Prior to the 2020 Lockdowns, Buy-Now-Pay-Later services were obscured from most of the market. Affirm was founded in 2012 by PayPal co-founder, Max Levchin, but was only used on high purchases by a small handful of merchants. After the 2020 Lockdowns, as people’s money became weaker, sudden partnerships with Apple Pay and Amazon, a Super Bowl ad and an IPO brought Affirm and the entire Buy-Now-Pay-Later scheme to a public already slipping into debt.

The first year saw an over four-hundred-percent increase in people using Buy-Now-Pay-Later services to buy essentials including groceries, gas, and paying their utilities.

Starting in 2024, Affirm has been gradually rolling out its new requirement for biometric identification. Once again, this is the old fashioned Problem-Reaction-Solution scheme being deployed. Under the guises of safety and fraud prevention, the Buy-Now-Pay-Later industry will soon require biometric ID. And Visa is following close behind. Visa launched their Payment Passkey in 2024, which allows you to voluntarily make purchases with your phone’s built-in biometrics.

Visa aims to be “biometric-first” by 2026. The International banking cartel has made it clear that this is where we are headed. It’s the only way the Crypto-AI control grid can function. While many of us can clearly see this as a major upgrade for tyranny and an affront to human free will, many are perfectly content with an authoritarian state. The 2020 Lockdowns seemed to have re-enforced this. …”

And Then There is the Rapid Increase of Drones Surveilling All Americans — Collection of Locations and Other Personal Data — For Sale to Third Parties

An FAA waiver issued last March made it legal for government agencies and local police to operate drones beyond a visual line of sight and over large crowds of people here in the US. And since then, California company Skydio is now deploying its quadcopter drones in just about every major US city. These drones have thermal imaging cameras, they are operated without a human user, and they have been deployed by Israel since October 2023 to track, trace, and murder tens of thousands of non-combatant Palestinians. The very same drones used by the US Department of War to surveil its enemies, the same drones used by Israel to ethnically cleanse what’s left of Palestine, are now being launched everyday in most major US cities to track and trace every individual. The new financial system is now ready to be born out of the ashes of the old. And all that will be required in order to buy and sell, will be your consent to the biometric digital ID.

Local Surveillance in Laconia

NONE of these RFPs and BIDS below (and there are more) includes what has been placed on towers, billboards, utility poles, and street light poles on easements owned now by “privatized” utility companies.

The Internet of Bodies (IOB) — One Main Market for Our Highly Personal Information, Surveilled, Gathered, Sold and Re-Sold by Public and Private Parties — Absent Consent

The author of this blog post researched the Internet of Things (IOT), the Internet of Bodies (IoB), and the Wide Area Body Network (WBAN). The project took over 2 years and it compiled over 300 pages of information resulting in a report for private discussion only.

This is not science fiction. The Internet of Bodies IOB is very real and operating all around us in the Lakes Region. WEF advocate Harrai “asserts” and Musk “acknowledges” in 2021 that this is the moment when personal privacy ended. Did you — the reader consent?

The systems are designed to make us programmed livestock without free choice — without moral agency. THAT’S THE DECEPTION. That’s the lie!

I produced this video a year of so ago in 2024 dealing with existing DNA programming technologies and more.

“Change the Thoughts | Social Media Videos Reel | Demystifying Natural Sciences for Laypeople”

The Law Enforcement Approach

For law enforcement — shared (footage and data scraping phones, laptops, cars) “for profit revenue” with third party corporations is a currently active public-private marketplace with extraordinary profit potentials;

The Real Threat of DNA Gathering. IDENTITY THEFT, IDENTITY COUNTERFEITING, IDENTITY SALE AND MALWARE OF SYNTHETIC CODES into humans

Is Surveillance and DNA gathering, and Hacking of DNA personal information on public and private data bases really a threat locally and nationally? The Short answer is YES!

A Long History of Surveillance and Motives in America

SOURCE: “In a striking new warning from cybersecurity and biotechnology experts, researchers have revealed that DNA hacking may soon become the next frontier in cyber warfare. A new study published in IEEE Access has identified critical security gaps in next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies that could expose highly personal genetic information to cyberattacks, espionage, and even biological sabotage.

According to the researchers, the surge in genomic data collection has outpaced the development of security frameworks to protect it. The result? Our most personal data—our DNA—is increasingly at risk of cyber exploitation.

“Genomic data is one of the most personal forms of data we have. If compromised, the consequences go far beyond a typical data breach,” co-author and microbiologist at the Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Women’s University, Dr Mahreen-Ul-Hassan, said in a statement. “If compromised, the consequences go far beyond a typical data breach.” NGS has revolutionized healthcare and biomedical research by enabling the rapid, cost-effective sequencing of DNA and RNA. Millions of people worldwide have used it for ancestry testing, disease diagnosis, cancer screening, and personalized medicine.

However, as the technology has accelerated scientific discovery and offered life-changing health insights, it has also opened Pandora’s box of cyber-biosecurity risks. This newly published study is one of the first to present a step-by-step threat analysis of the entire sequencing pipeline—from raw data generation and sample preparation to cloud-based analysis and data interpretation—exposing a range of novel vulnerabilities unique to the NGS process.

Study authors, including researchers from the UK, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan, describe a landscape in which genomic data, unlike any other digital record, is both permanent and deeply personal. A stolen credit card can be replaced, they note. However, if your information is compromised by DNA hacking, there’s no taking it back. Once it’s out, it’s out forever.

One of the study’s most alarming revelations is the possibility of DNA hacking, where DNA itself is used as a vehicle to carry malicious code. In an earlier proof-of-concept experiment, scientists demonstrated that it is theoretically possible to encode malware into synthetic DNA. When sequenced, the biological sample could produce digital output that exploits vulnerabilities in bioinformatics software, ultimately allowing an attacker to gain unauthorized access to the sequencing computer.

This type of DNA hacking is not just conceptual. A research team at the University of Washington successfully demonstrated it, making it the first instance of DNA being used to breach a computer system. The implications are profound: a malicious DNA strand could disrupt a lab’s sequencing run or compromise a hospital’s genomic database.

Another vulnerability lies in the re-identification of supposedly anonymous genomic data. Even when names are removed, researchers have shown that DNA samples—especially those containing short tandem repeats, or STRs—can be cross-referenced with public genetic genealogy databases to infer surnames and other identifying information.

When combined with publicly available demographic data like age and zip code, this can lead to successful re-identification of individuals. In one case, between 84% and 97% of participants in the Personal Genome Project were re-identified using this method. This kind of breach doesn’t just violate privacy—it has real-world consequences, including risks of blackmail, discrimination, and medical fraud.

The study also explores how emerging technologies, especially artificial intelligence, may inadvertently accelerate these risks. With AI capable of bridging complex gaps in knowledge, adversarial actors could use AI tools to generate attack strategies that exploit specific vulnerabilities in bioinformatics pipelines.

The authors express concern that AI could be used to generate malicious code, manipulate DNA synthesis orders, or design custom malware that targets the computational tools responsible for analyzing genomic data.

The research references real-world case studies that underscore the urgency of these risks. Recent cyberattacks on healthcare and pharmaceutical companies have demonstrated the potential for devastating breaches.

For instance, in 2024, Octapharma Plasma in the U.S. suffered a ransomware attack that compromised sensitive personal information. Similarly, Japanese pharmaceutical firm Eisai faced massive logistical and production delays after a cyberattack disrupted their systems.

Although these attacks did not directly involve sequencing data or DNA hacking, they highlight how vulnerable biotech and healthcare infrastructures remain to digital exploitation. As sequencing becomes more integrated with clinical practice and public health infrastructure, it is only a matter of time before NGS platforms become a direct target.

One of the study’s most significant contributions is the introduction of a new cyber-biosecurity taxonomy designed explicitly for next-generation sequencing. Unlike conventional cybersecurity models, which focus on network vulnerabilities and software flaws, this new framework extends into the biological domain. It identifies specific threat vectors at every stage of the NGS workflow.

These include synthetic DNA-based malware attacks, sample multiplexing exploitation, adversarial manipulation of sequencing workflows, and inference attacks that exploit genomic linkage disequilibrium to predict health conditions from partial DNA sequences.

The authors explain that each phase of the NGS workflow presents its own unique set of vulnerabilities. In the initial stages, where DNA is extracted from samples such as blood or tissue, threats like re-identification attacks and physical theft of biological material can occur.

Even manual handling procedures are not immune. If an insider tampers with or substitutes a sample during extraction, it could corrupt the entire sequencing process and lead to dangerous or misleading conclusions in clinical or forensic contexts.

The study outlines several cyber risks during the library preparation stage, where DNA fragments are processed and tagged for sequencing. Automated liquid handling robots and barcode tracking systems used in high-throughput labs often rely on connected software platforms.

If these are compromised—whether through malware, ransomware, or a supply chain attack—the integrity of genetic data can be irreparably damaged. The study also describes multiplexed DNA injection attacks, where a malicious DNA sample introduced into a pooled batch can manipulate sequencing outcomes or cause misattribution of genetic material across different samples.”

36 page Article — DNA THEFT: RECOGNIZING THE CRIME OF NONCONSENSUAL GENETIC COLLECTION AND TESTING, by ELIZABETH E. JOH∗

SOURCE: Boston University Law Review Article “The fact that you leave genetic information behind on discarded tissues, used coffee cups, and smoked cigarettes everywhere you go is generally of little consequence. Trouble arises, however, when third parties retrieve this detritus of everyday life for the genetic information you have left behind. These third parties may be the police, and the regulation over their ability to collect this evidence is unclear.

The police are not the only people who are interested in your genetic information. Curious fans, nosy third parties, and blackmailers may also hope to gain information from the DNA of both public and private figures, and collecting and analyzing this genetic information without consent is startlingly easy to do. Committing DNA theft is as simple as sending in a used tissue to a company contacted over the internet and waiting for an analysis by email. A quick online search reveals many companies that offer “secret” or “discreet” DNA testing.

The rapid proliferation of companies offering direct-to- consumer genetic testing at ever lower prices means that both the technology and incentives to commit DNA theft exist.

Yet in nearly every American jurisdiction, DNA theft is not a crime. Rather, the nonconsensual collection and analysis of another person’s DNA is virtually unconstrained by law. This Article explains how DNA theft poses a serious threat to genetic privacy and why it merits consideration as a distinct criminal offense.

INTRODUCTION

The fact that you leave genetic information behind on discarded tissues, used coffee cups, and smoked cigarettes everywhere you go is generally of little consequence. Trouble arises, however, when third parties retrieve this detritus of everyday life for the genetic information you have left behind. These third parties may be the police, and the regulation over their ability to collect this evidence is unclear.1

The police are not the only ones who are interested in other people’s genetic information. Consider:

The political party that is interested in discovering and publicizing any predispositions to disease that might render a presidential candidate of the opposing party unsuitable for office.2

An historian who wishes to put to rest rumors about those who claim to be the illegitimate descendants of a former president but refuse to submit to genetic testing.3

A professional sports team that wants to analyze the genetic information of a prospective player, despite his protests, to screen for risks of fatal health conditions before offering him a multi-million dollar contract.4

An individual’s personal enemy who would be thrilled to analyze the genetic information of his target and post information on the internet about the target’s likelihood of becoming an alcoholic, a criminal, or obese.5

A wealthy grandparent who suspects that a grandchild is not genetically related to her and plans to disinherit him if that is the case.6

A person involved in a romantic relationship who wants to find out whether his partner carries the gene for male pattern baldness or persistent miscarriage.7

A couple who would like to know if their prospective adoptive child has any potential health issues before they make a final decision.8

Fans who would pay a high price to buy the genetic information of their favorite celebrity.9

If any of these curious people want to act, they can. A quick search of the internet unearths many companies that offer “secret” or “discreet” DNA testing.10 An undercover investigation by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) in 2010 reported that representatives of two of the fifteen companies it targeted specifically suggested the use of surreptitious and nonconsensual genetic testing.11 The proliferation of direct-to-consumer DNA tests that are increasingly inexpensive and readily accessible means that these third parties may attempt to collect and analyze anyone’s DNA without consent.12 Companies like 23andMe, Navigenics, and deCODEme promise to identify predispositions to various diseases and health conditions.13 A saliva DNA collection kit bought at your local Walgreens for less than three hundred dollars might be just around the corner.14

What is more, in most American jurisdictions, the nonconsensual collection of human tissue for the purposes of analyzing DNA, or “DNA theft” as I will call it, is not a crime (or even a civil violation for that matter). While a number of states and the federal government ban the disclosure of genetic testing

What’s Actually at Stake Motivating the Rapidly Expanding Surveillance by Public-Private Partnerships?

In one word it’s “BioPiracy” described below

Let’s begin with several current 2025 international reports on copyright legislation in Denmark.

VIDEO LINK TO FIRST THUMBNAIL BELOW.

ARTICLE LINK TO SECOND GRAPHIC BELOW

ARTICLE LINK TO THIRD GRAPHIC BELOW REPORTED BY NORTH CAROLINA LAW FIRM: TED LAW

SOURCE: “In a world increasingly shaped by artificial intelligence and generative AI, the misuse of AI-generated content has become a pressing global concern. Denmark has made history by passing a copyright bill of Denmark that grants citizens full ownership rights over their personal likenesses , including their face, voice, and body. This new copyright framework addresses threats posed by deepfake technology, synthetic media, and digital imitations, while reinforcing digital rights and digital identity protection in the age of AI Deepfakes.

The legislation empowers individuals to submit a takedown request or takedown notices against unauthorized uses of their digital representation, pursue civil enforcement and infringement proceedings, and hold digital platforms and online platforms accountable. It’s a major step toward safeguarding likeness rights and personality rights, especially as Denmark prepares to assume the EU presidency , a moment that could influence EU copyright law and future AI regulation across the European Union.

The Rise of Deepfake Laws in the Age of Generative AI

Deepfake creators have leveraged neural network and artificial neural network models to create convincing deepfake video clips, face swaps, and manipulated image content. These computer-generated images can impersonate a performing artist, political leader, or public figure to spread fake news, launch deepfake scandals, or run scam campaigns.

Cases have ranged from deepfake scam phone calls using cloned voices to political content fabrications aimed at eroding public trust. The problem has escalated beyond digital self reputation damage , it now poses serious risks to biometric security, biometric features theft, and even identity theft.

Denmark’s Legal Solution and Platform Responsibility

The new copyright protection measures are groundbreaking. By recognizing human authorship over one’s digital replica, Denmark affirms that digital assets like a person’s likeness are protected under intellectual property law.

The law mandates platform responsibility by requiring online platforms and digital platforms to respond swiftly to takedown request submissions. Failure to comply could result in severe fines, infringement proceedings, and civil enforcement.

It also introduces a legal pathway for content removal and monetary remedies for reputation damage caused by unauthorized synthetic media and AI-generated deepfakes.

Implications for the European Commission and Beyond

As Denmark takes the lead ahead of its EU Council presidency, this legislation could guide the European Commission toward a unified AI governance and privacy laws framework. Such integration could strengthen international cooperation to address cross-border deepfake laws enforcement.

The law complements measures like the Digital Services Act, UK GDPR, and even EU Trade Marks protections, reinforcing the message that digital rights are a fundamental part of modern governance.

Technology at the Heart of AI Regulation

To enforce these protections, Denmark is expected to work with Legal Tech innovators and AI content labels to detect AI-generated content. This may include deep learning detection systems, digital copy machine watermarking, and collaboration with the influencer marketing industry to ensure that branded content and brand ambassadors use authorized likenesses only.

Even pop culture references, like Star Wars characters portrayed by the 501st Legion Ireland Garrison, have been involved in debates about digital representation rights, showing how far-reaching the issue is , from a performing artist to an AI character in a gaming environment.

Risks of Unchecked Synthetic Media

Without robust safeguards, synthetic media can be exploited in scam campaigns targeting the cryptocurrency community or manipulated to defame brand ambassadors. Gambling Commission investigations have shown how manipulated promotional materials can mislead consumers.

Even celebrities like Anil Kapoor have taken legal action to protect their personality rights, highlighting that the problem spans industries and borders.

Enforcement Challenges and International Cooperation

While the law is ambitious, its success depends on international cooperation. Many deepfake technology operators are outside Denmark’s jurisdiction. Collaborative efforts with entities like the US Senate, Unified Patent Court, and UPC Arbitration Centre may be essential.

Key obstacles include:

Tracking deepfake creators across multiple jurisdictions.

Distinguishing human authorship from machine-generated work.

Preventing misuse of AI character or digital self likeness for malicious purposes.

Protecting the Digital Self in the Era of AI Governance

This copyright law reinforces the principle that in the world of AI-generated deepfakes, each person owns their own digital self. From influencer marketing industry disputes to protecting performing artist rights, the shift is toward greater personal control over digital assets.

It also signals to deepfake creators that misusing personal likenesses without consent can lead to severe fines and infringement proceedings under evolving privacy laws and AI governance regulations.

Conclusion

Denmark’s proactive approach could become the gold standard for deepfake laws in the European Union. By integrating strong copyright protection, platform responsibility, and digital identity protection measures, it addresses the risks posed by AI-generated deepfakes and strengthens public trust in the digital age.

If widely adopted, this model could harmonize AI regulation across borders, empowering individuals and deterring misuse of digital representation.

About Ted Law

Ted Law Firm , closely follows developments in copyright law, privacy laws, and AI regulation that affect individuals worldwide. We serve families across Aiken, Anderson, Charleston, Columbia, Greenville, Myrtle Beach, North Augusta and Orangeburg. By understanding changes in legislation like Denmark’s copyright bill of Denmark, the firm ensures its community remains informed and prepared for the challenges posed by AI-generated deepfakes and synthetic media. Contact us today for a free consultation. For more information and a A DEEPER DIVE

So Now Let’s Turn to the “Real Motives” for Surveillance Collection and Sale of Personal Data — There’s a Long History to This — One Which is not Generally Know by the Public.

This topic of the covert theft (BioPiracy) through surveillance of human data face, body, voice, DNA sequences and pathway processes; is now a massive and highly profitable market. Some refer to it as a “Wild West” environment which is currently unregulated in America — and IF regulated at all, those public-private partnerships “so regulated” are stakeholders in the profits bonanza.

In 2024, I wrote and published a 32 page article (separate blog) on this subject by itself entitled:

“ENVIRONMENTAL AND EPIGENETIC IMPACTS | “BIOPIRACY” AND PATENTS ON: “INDIVIDUAL HUMAN” GENOMES, MICROBIOME ORGANISMS’ GENOMES | PLANT GENOMES | ANIMAL GENOMES | AS OF 1994-2024 AND “GENE DRIVES” by Jeffrey Thayer (September 2024).”

The actual blog post is recommended (with helpful videos) here at this LINK:

These are not mere theoretical questions and are continuing to be litigated today in a variety of settings revealed in this article:

How recent court cases are testing the limits of N.H.'s constitutional right to privacy — which includes face, voice, body, and genetic information covertly gathered, used and sold.

“Four years ago, New Hampshire voters overwhelmingly approved a new amendment to the state's constitution enshrining a “right to live free from government intrusion in private or personal information. … Staters revealed:

“What counts is personal information is a very large universe,” he said. “Is what Internet sites you go to personal information?… Is what books you take out of the library personal information? … SB418 is facing two separate lawsuits, each citing the state’s new privacy amendment as part of their arguments for why it should be overturned.” SOURCE See also: “Ballot Question 2: Should 'Right to Live Free' Language Be Added to the N.H. Constitution?”

“The second ballot question addresses the individual right to privacy from the state in reference to personal information and data. …

This amendment would add language to the New Hampshire Constitution stating that "an individual's right to live free from government intrusion in private or personal information is natural essential and inherent." So what does that mean? …

Do we know what is considered information then under this? Are we talking about DNA, and passwords, and online data and that kind of thing? What are we talking about here?

Well that's what will be worked out. That will be worked out on a case by case basis, because as you pointed out, the language is abstract and one can envision all sorts of emerging disagreements about the meaning of this language in different contexts. …”

Some of many other cases winding their way through various courts include:

A federal lawsuit filed by the Institute for Justice against the Virginia city of Norfolk, challenging the city’s widespread deployment of Flock Safety Automated License Plate Recognition (ALPR) cameras.

The lawsuit argues that the city’s installation of more than 170 cameras on public roads constitutes an unconstitutional, warrantless surveillance program that monitors every motorist, raising questions about digital privacy and government overreach.

Flock Safety’s Different Approach to ALPR Technology

Flock Safety, the company whose ALPR systems are central to this lawsuit, differs from traditional ALPR providers in several ways. Traditional ALPR systems are generally focused on reading license plates using infrared cameras and feeding this information into central databases.

Flock Safety’s technology goes further, capturing additional details such as vehicle make, model, color, and other distinguishing characteristics like bumper stickers. This comprehensive approach allows law enforcement to track and identify vehicles more effectively, even when plates are obscured or altered .

However, this detailed data collection raises concerns about prolonged monitoring and data retention. The lawsuit claims that these cameras, which are designed to retain data for extended periods, allow law enforcement to effectively track the movements and activities of residents without individualized suspicion. Plaintiffs argue that this aggregated data creates a detailed historical record of every vehicle, infringing on privacy rights.

… Tracking and Historical Data Logging:

Flock’s systems collect and retain a rich dataset that could be used to trace a vehicle’s history over time. Such detailed records raise legal questions about whether long-term surveillance without a warrant constitutes a violation of Fourth Amendment protections, especially when public movements are aggregated and analyzed to reveal patterns and connections . SOURCE See further: National Law Review “Hidden Camera Lawsuits” by: Lawrence J. Buckfire of Buckfire Law Tuesday, April 11, 2023

“Slater Slater Schulman LLP Files Lawsuits on Behalf of Over 400 Victims of Hidden Camera Surveillance at Northwell Health Facilities” NEWS PROVIDED BY Slater Slater Schulman LLP Sep 25, 2025, 11:03 “Employee Used False Smoke Detectors to Record Patients and Visitors in Bathrooms and Changing Rooms for Nearly Two Years.

SOURCE: NEW YORK, Sept. 25, 2025/PRNewswire/ -- Northwell Health and its affiliated entities are being named in multiple civil complaints alleging negligence that enabled the secret recording of over 400 patients and visitors, including children, while they were undressed in bathrooms and changing rooms at two Long Island medical facilities. As alleged in the complaints, the healthcare system failed to detect and prevent unlawful surveillance that continued for nearly two years, despite numerous warning signs that should have alerted management to suspicious activity. The lawsuits were filed in Nassau County Supreme Court by attorneys at Slater Slater Schulman LLP, a leading, full-service law firm with decades of experience representing survivors of traumatic and catastrophic events.

According to the complaint, from early August 2022 through late April 2024, Sanjai Syamaprasad was a licensed sleep technician employed by Northwell Health. According to the facts in his separate felony criminal case in NassauCourt Supreme Court, Syamaprasad installed hidden video cameras inside false smoke detectors throughout staff and patient bathrooms and changing rooms at the Northwell Health Sleep Disorders Center and STARS Rehabilitation in Great Neck, during which time thousands of patients, including children, were recorded without their knowledge or consent while in states of undress.

In July, Syamaprasad pleaded guilty to five counts of Unlawful Surveillance in the Second Degree and two counts of Tampering with Physical Evidence. He is expected to be sentenced to five years probation as part of a pre-negotiated plea.

"The mediocre sentence in this criminal case doesn't even amount to a wrist slap – it's a complete miscarriage of justice," said Adam Slater, Founding and Managing Partner of Slater Slater Schulman LLP. "The only way that the victims of Northwell Health Sleep Disorders Center will ever receive true justice is through the civil courts. While Northwell's carelessness represents an egregious breach of patient privacy and trust, Slater Slater Schulman LLP has a very strong track record of achieving results for patients who have been harmed by medical institutions."

In December 2021, Slater Slater Schulman LLP was the first law firm to reach an agreement with Columbia University and NewYork-Presbyterian on behalf of patients of convicted gynecologist Robert Hadden. This advocacy resulted in the creation of a $71.5 million compensation fund for 79 Slater Slater Schulman clients. As stated in the complaints filed by Slater Slater Schulman in Nassau County Supreme Court, despite discovering the unlawful surveillance in April 2024, Northwell Health waited more than a year before notifying potential victims, only sending notification letters in late May 2025. This delay prevented victims from taking timely action and caused additional emotional distress when they learned of the violations.

The lawsuits, filed in Nassau County Supreme Court, allege multiple counts of negligence against Northwell Health entities, including negligent hiring, training, retention, and supervision of Syamaprasad. The complaints assert that Northwell Health failed to maintain adequate security measures, conduct proper background checks, and implement policies to prevent such conduct despite having statutory duties under HIPAA and other regulations to protect patient privacy and confidentiality. …”

See also: NSA Surveillance and Section 702 of FISA: 2024 in Review, DEEPLINKS BLOG , BY MATTHEW GUARIGLIA, DECEMBER 28, 2024

Surveillance is Not a New Program. It dates back to the 16th Century and Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon.

The Emergence of the “all seeing eye” and the Panopticon Surveillance

Is the Opticon the original Blueprint for “15 Minute” Cities?

Just the last four slides above are revealing. Bentham’s Opticon vision was not limited to just prisons. His “syndics” were offered as a method to surveil the general public on everyday streets. Some readers may recognize this in all the recent concerns being identified with various presentations of “15 Minute Cities”.

The author Foucault describes the Panopticon in his famous work Discipline and Punish (1975). While the Panopticon is a model for a prison designed by the English philosopher Jeremy Bentham, Foucault sees it as much more than that. For Foucault the Panopticon is an architectural figure -- a kind of metaphor -- for modern power relations in general.

As Foucault describes it, in the modern world, power circulates around us through systems of surveillance and self-discipline. We are constantly being watched, measured, and evaluated, and even when we are not, we feel as if we are, and so we conduct ourselves and discipline ourselves into behaving in particular ways. This is how modern power dynamics work and they can be effectively illuminated by Bentham's Panopticon design. For more on the ROOTS panopticon greatest good collectivism Bentham. monograph quotes LINK:

A follow-up to this blog post is in research concerning the “Shock Doctrine” — its history and its connections to data gathering and surveillance for profit amid “disasters”. To read ahead so to speak, please watch this 2009 documentary video featuring journalist Naomi Klein:

FOR MORE INFORMATION on TEAM CONNECTED’s outreach mission and other blog posts please visit HERE.