What Does the American History of HOUSELESSNESS Have to Do With Anything in the Lakes Region?

OVER 20 HOUSELESS programs have been instituted since the 1850’s — and more previously — in Colonial America

WARNING: If readers do not enjoy reading and research — this Blog Post may not be for you. Not sure? Skim quickly to see where we are headed, and perhaps go back to the beginning.

[Est. read time: 45 minutes]

Those in journalist circles speak about the “buried lead” of any reported story. That’s the portion of an article “beneath the fold” where the relevant facts are given to support the headline. This is a lengthy Blog Post.

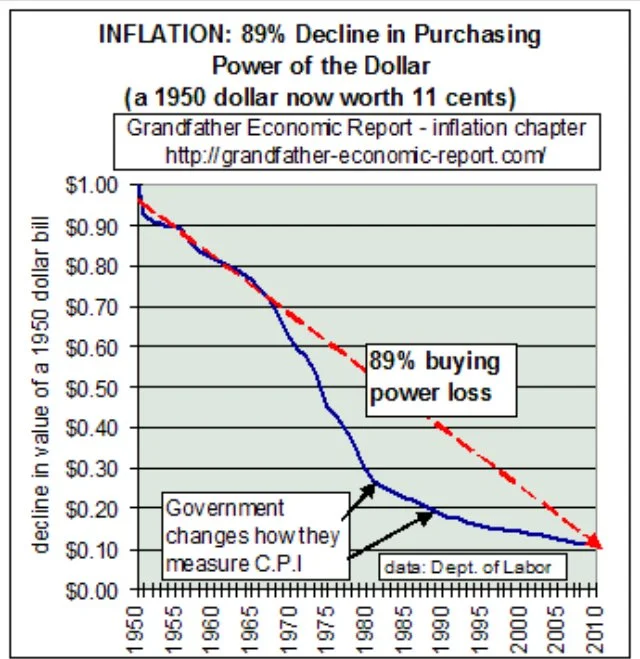

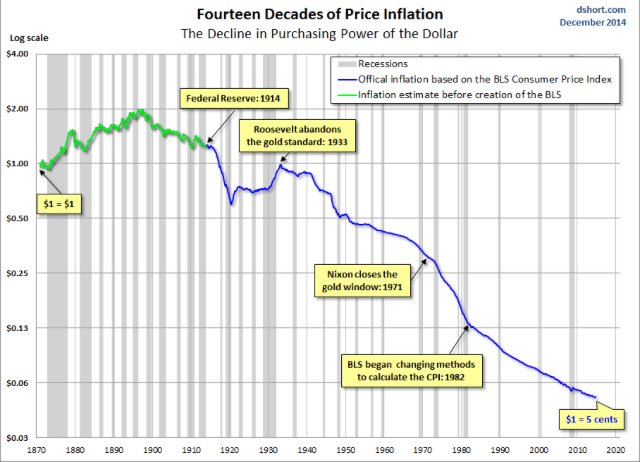

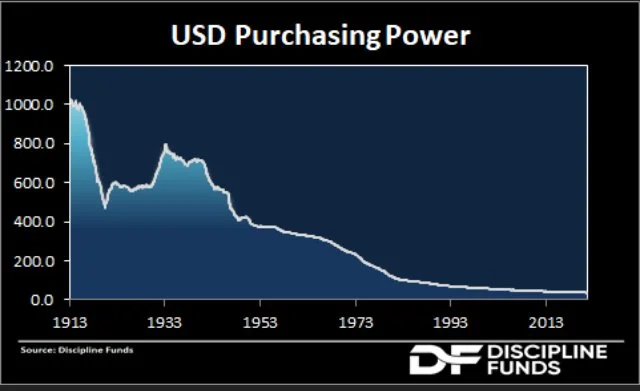

That is because the subject matter requires more than a few sentences. THERE IS an American Legacy of HOUSELESS laid out in detail below. THERE IS also an American Legacy of unsustainable national, colonial and state debt (beginning in the late 1600’s. Both are part of America’s Legacy. Today policymakers continue debates over the widening gap between Americans being “Rent Burdened” — meaning a rapidly increasing GAP between incomes, rent and other daily expenses. [See our previous BLOG POST. “Rent Burdened”? | One Paycheck Away? | Already There in the Lakes Region!”]

These debates also have a long, cyclical history in our America’s Legacy — where financial difficulties of Americans (from the 1600’s) forward to today. HOUSELESSNESS and “Rent Burdens” blamed on inflation of prices and deflation of “paper currency” purchasing power. The word salads used by policymakers to define inflation and deflation are also not new; and that is presented in detail below.

These two recurring American Experiences have been interconnected since the settlement of this country.

The journalists’ “buried lead” in the American Legacy of HOUSELESSNESS is our common history and experiences with HOUSELESS community members. Readers will learn here that HOMELESSNESS and unsustainable national debt’s recurring history — dates back to medieval England “debt peonage” — and it carries forward consistently through colonial America; and then through the Revolution, then to the pre and post Civil War era, to WW1, the Great Depression (Hoovervilles) and through the 1960’s and to our present experiences today.

Some may ask, why do I need to know this now? ANSWER: Maybe you don’t — unless you want to address the root cause.

WHY? Some aspects of the human nature of our ancestors addressing HOMELESS folks are being heard today in 2025. Echoing the past, that includes words to the effect:

that some people were “worthy” of help while others were not;

that in the American colonial days, laws “sorted people into different groups” based on why they were poor, and treated them differently depending on whether their poverty was seen as “deserved” or “undeserved”;

that in early settlement days, communities only offered aid to the poorest men and women — if they entered workhouses—that is, harsh institutions where they were forced to perform exhausting and often degrading labor. These policies, and the values behind them, heavily influenced how early American settlers treated people experiencing poverty and homelessness.

Modernly we are apt to hear phrases such as: “I’m in favor of giving folks a hand up but NOT a hand out.” But we’re NOT likely to hear WHAT exactly defines the “hand up” and what defines the “hand out”.

APPENDIX PDF TO THIS POST:

STRUCTURE OF POST: An appendix (AT THIS LINK) has been prepared for this BLOG POST. It is entitled: Appendix to a TEAM CONNECTED Blog Post (09.10.2055) for readers reference to address our opening question:

“What Does the American History of HOUSELESSNESS Have to Do With Anything in the Lakes Region?”

The Appendix is excerpted from a 1275 page “unpublished” Monograph entitled: “Why?” | A “Private” Study Guide On What is “the Law?”

Background of the Monograph: In 2023, the author of this blog post began research and writing task of answering a simple question: “What is the Law”? The Table of Contents to the Monograph begins on page 20 of the Appendix for context.

Space limitations in a Blog Post prevent the insertion of the content of the Appendix (36 pages) into the body of the Blog Post (i.e., comprising numerous pages with a large number of linked footnotes to primary sources).

To repeat, our shared American Legacy of HOUSELESSNESS is directly connected to another shared historical experience which includes: colonial, state and national debt, inflation, and inflation/deflation of bills of credit (i.e., currency or “paper money”) — and both are tied to Americans’ progressive, cyclical, inability to pay everyday debts (i.e., rents, mortgages, energy bills, medical expenses, food, &c.).

This cyclical American Experience is not new and is presented in greater detail below in this Blog Post. These subjects were also touched upon in a previous Blog Post by TEAM CONNECTED entitled: “Rent Burdened”? | One Paycheck Away? | Already There in the Lakes Region!” (09.03.2025). Some have observed:

“History is a set of lies agreed upon.” Napoleon Bonaparte

“The only thing new in the world is the history you do not know” Harry Truman

“History doesn’t just repeat itself, it rhymes.” Mark Twain

“[L]’histoire est juste peut-être, mais qu’on ne l’oublie pas, elle a été écrite par les vainqueurs” “[T]he history is right perhaps, but let us not forget, it was written by the victors” AD 1842, quoted later by Winston Churchill

[A FRESH PERSPECTIVE]:

‘… In the early 1900’s Hudson Maxim[1], an author (not well-know today, but very well-known at that time), wrote a 324 page book entitled “Defenseless America” (AD 1912). Maxim’s observations of life in 1912 are particularly relevant to the HOUSELESS today — and their gathering in encampments in forests and fields — as a means of self-preservation. In the Preface, Maxim presents a “First Principle” of “the Law”: “the Law of Self-Preservation” and then warns:

“The main object of this book is to present a phalanx of facts upon the subject of the defenseless condition of this country, and to show what must be done, and done quickly, in order to avert the most dire calamity that can fall upon a people—that of merciless invasion by a foreign foe, with the horrors of which no pestilence can be compared. We should bring a lesser calamity upon ourselves by abolishing our quarantine system against the importation of deadly disease and inviting a visitation like the great London Plague, or by letting in the Black Death to sweep our country as it swept Europe in the Middle Ages, than by neglecting our quarantine against war, as we are neglecting it, thereby inviting the pestilence of invasion.

Self-preservation is the first law of Nature, and this law applies to nations exactly as it applies to individuals. Our American Republic cannot survive unless it obeys the law of survival, which all individuals must obey, which all nations must obey, and which all other nations are obeying. No individual, and no nation, has ever disobeyed that law for long and lived; and it is too big a task for the United States of America.

It is the aim of this work to discover truth to the reader, unvarnished and unembellished, and, at the same time, as far as possible, to avoid personalities. Wherever practicable, philosophic generalizations have been tied down to actualities, based upon experiential knowledge and innate common-sense of the eternal fitness of things. The strong appeal of Lord Roberts for the British nation to prepare for the Armageddon that is now on, which he knew was coming, did not awaken England, but served rather to rouse Germany. …”

On another, but highly related set of subjects examined throughout the Monograph; that is, ius naturae (i.e., the laws of nature, human nature), immediately below, Maxim provides the insights about human nature not changing — in AD 1912 and as well for today. In terms of historiography, given the known reputation of Hudson Maxim, his inventions such as smokeless gunpowder which he sold to DuPont, and the Maxim gun; what are the chances that President Woodrow Wilson and his closest administrator Edward Mandell House (author of “Philip Dru, Administrator”, AD 1913[2]) had not read, or were fully briefed, on the Maxim’s book “Defenseless America” (including the numerous public Editorial Reviews of the book in (fn 14 above)?

Considering the question, readers will recall this to be coterminous to America preparing for World War I, the passage of the Federal income tax act, the federal reserve act, and the primary source private papers of House’s conversations with Wilson concerning: “[Americans will be] “… required to register their biological property in a National system designed to keep track of the people and that will operate under the ancient system of pledging. By such methodology, we can compel people to submit to our agenda, which will affect our security as a charge-back for our fiat '“paper currency”. Every American will be forced to register or suffer not being able to work and earn a living. They will be our chattel, and we will hold the security interest over them forever, by operation of the law merchant under the scheme of secured transactions. …” This is addressed on more depth subsequently in this Monograph at this subheading link in MONOGRAPH:

“… We Americans expect to get all we want any way, either with or without arbitration. If we expected that the Chinese would be forced upon [40] us, or our rights and privileges curtailed in the Orient, we should not think of joining in an arbitration pact for a minute. There will always be the warfare of commerce for the markets of the world, and it will be tempered with avarice, not mercy; and commercial warfare will become more and more severe as the nations grow, and as competition, with want and hunger behind it, gets keen as the sword-edge with the crowding of people into the narrow world. …

"[Very] soon, every American will be required to register their biological property in a National system designed to keep track of the people and that will operate under the ancient system of pledging. By such methodology, we can compel people to submit to our agenda, which will affect our security as a charge-back for our fiat paper currency. Every American will be forced to register or suffer not being able to work and earn a living. They will be our chattel, and we will hold the security interest over them forever, by operation of the law merchant under the scheme of secured transactions. Americans, by unknowingly or unwittingly delivering the bills of lading to us will be rendered bankrupt and insolvent, forever to remain economic slaves through taxation, secured by their pledges. They will be stripped of their rights and given a commercial value designed to make us a profit and they will be none the wiser, for not one man in a million could ever figure our plans; and, if by accident one or two would figure it out, we have in our arsenal plausible deniability. After all, this is the only logical way to fund government, by floating liens and debt to the registrants in the form of benefits and privileges. This will inevitably reap to us huge profits beyond our wildest expectations and leave every American a contributor to this fraud, which we will call "Social Insurance (SSI)". Without realizing it, every American will insure us for any loss we may incur, and in this manner every American will unknowingly be our servant, however begrudgingly. The people will become helpless and without any hope for their redemption; and we will employ the high office of the President of our dummy corporation to foment this plot against America." Stamper, supra, p. 59. SECOND SOURCE:

Unchanging Human Nature

[1912] “… Human nature is the same today as it was in the ante-rebellion days of human slavery. It is the same as it was when Napoleon, with the will-o'-the-wisp of personal and national glory held before the eyes of emotional and impressionable Frenchmen, led them to wreck for him the monarchies of Europe. Human nature is the same today as it was in Cæsar's time, when he massacred two hundred and fifty thousand Germans—men, women, and children—in a day, in cold blood, while negotiations for peace were pending, and entered in his diary the simple statement, "Cæsar's legions killed them all." Human nature is the same today as it was in the cruel old times, when war was the chief business of mankind, and populations sold as slaves were among the most profitable plunder. Yes, human nature is the same [41] as it has always been. Education and Christian teaching have made pity and sympathy more familiar to the human heart, but avarice and the old fighting spirit are kept in leash only by the dominance of necessity and circumstances, which the institutions of civilization impose upon the individual. …”

The following is quoted from "Origins and Destiny of Imperial Britain," by the late Professor J. A. Cramb: "War may change its shape, the struggle here intensifying it, there abating it; it may be uplifted by ever loftier purposes and nobler causes. But cease? How shall it cease?

"Indeed, in the light of history, universal peace appears less as a dream than as a nightmare, which shall be realized only when the ice has crept to the heart of the sun, and the stars, left black and trackless, start from their orbits."

Max Müller has told us that the roots of some of our words are older than the Egyptian Pyramids. Far older still are the essential traits of human nature. The human nature of today will be the human nature of tomorrow, and the human nature of tomorrow will be in all essential respects the same as it was in ancient Rome, Persia, and Egypt, and even in the palmy days of sea-sunk Atlantis. [42]

The best of us are at heart barbarians under a thin veneer of civilization, and it is as natural for us to revert to barbarous war as for the hog to return to his wallow.

If we were able to apply to the upbuilding of our Army and Navy the money that goes to political graft throughout the country, and the money that has been squandered, and is still being squandered through our notorious vote-purchasing pensions, we could place ourselves upon a war footing that would be an absolute guarantee of permanent peace. It is not, therefore, very encouraging, to enlarge this failing system of laws, in order to save an annual expenditure certainly less than what the defects of our laws now cost the country. Even though international wars may be prevented by a court of arbitration, can rebellion and civil war be prevented, and ought they always to be prevented?

FOOTNOTES:

[1] WIKIPEDIA Reports: Hudson Maxim (February 3, 1853 – May 6, 1927), was an American inventor and chemist who invented a variety of explosives, including smokeless gunpowder, Thomas Edison referred to him as "the most versatile man in America". He was the brother of Hiram Maxim, inventor of the Maxim gun and uncle of Hiram Percy Maxim, inventor of the Maxim Silencer. … Maxim wrote a book, Defenseless America, first issued in 1912, in which he pointed out the inferiority of the American defense system and the vulnerability of the country against attacks of foreign aggressors. At that time, the United States army according to Maxim, had a total strength of 81,000 men of which 29,000 were assigned to man coastal artillery batteries at major ports. Later he joined his brother Hiram Stevens Maxim's workshop in the United Kingdom, where they both worked on the improvement of smokeless gunpowder. After some disputes, Hudson Maxim returned to the United States and developed a number of stable high explosives, the rights of which were sold to the DuPont company. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hudson_Maxim

AMERICAN EDITORS GIVING A REVIEW OF MAXIM’S BOOK STATED IN AD 1912-16:

From The New York American “One of the most remarkable men of our time has written a book—and the book is probably the most startling document ever placed before the American people. Its author is Hudson Maxim, world-famous inventor, writer on many topics of public interest, member of the Naval Advisory Board—and an American patriot. His book, called "Defenseless America," has fallen among the complacent, the self-satisfied, the careless and the indifferent like a seventeen-inch shell. It is a pitiless book—pitiless in its facts, pitiless in its logic, pitiless in its conclusions. Mr. Maxim knows what he is writing about; he is one of the greatest authorities on military affairs in the world. His book has the cold steel precision of truth. He shows that all wars have economic causes, no matter how they are painted over with sentiment. And he demonstrates that one of the most urgent economic incentives to war that has ever existed will be the relative condition of Europe and the United States at the close of the Great War. Imagine the victors of this gigantic conflict—Allies or Teutons—impoverished in money and resources, with the most colossal public debt in the world's history hanging over them, but possessing an enormous army of trained veterans and a world-beating navy. Then, on this side of the Atlantic, a nation that thinks it "can whip all creation," and acts on that principle—a hundred million over-fed, money-making people, nine-tenths of whom could not load a modern infantry rifle if they should ever happen to see one; a country of countless dollars protected by obsolete battleships and submarines that can neither float nor sink; a nation rich but undefended, confident but weak, dictatorial in manner but powerless in action. America sits on an open powder barrel. Will the Victors of the Great War apply the match? Get this stirring and tremendous book, and read what will happen—in Mr. Maxim's own words. He will tell you where the match will be applied, what points in controversy will bring on the collision—and then what will take place with startling swiftness. And— He tells what may be done, even at this late day, for effective defense.

New York American: "No book issued on the subject marshals with equal skill so great an array of facts as Mr. Maxim's volume. In the present state of national thought upon our military and naval needs this book is most valuable."

Los Angeles Times: "A powerful book on an imminent and national problem that every thinking citizen should read with care."

Baltimore Sun: "The book is brilliantly written, with the severity of one who intensely desires to drive a truth home and with the assurance of one who feels his statistics unassailable and his arguments unanswerable. He is supported by many witnesses whose knowledge must be respected. There is no smallness in the writer's attitude. He appears to feel intensely his mission as prophet and patriot."

[2] “Philip Dru, Administrator” “Philip Dru: Administrator: A Story of Tomorrow, 1920-1935 is a futuristic political novel published in 1912 by Edward Mandell House, an American diplomat, politician, and presidential foreign policy advisor. The book's author was originally unknown with an anonymous publication, however House's identity was revealed in a speech on the Senate floor by Republican Senator Lawrence Sherman.[1] According to historians, House highly prized his work and gave a copy of Dru to his closest political ally, Woodrow Wilson, to read while on a trip to Bermuda.[2][3][4]Set in 1920–1935,[16] Historian Paul Johnson wrote: "Oddly enough, in 1911 he [House] had published a political novel, Philip Dru: Administrator, in which a benevolent dictator imposed a corporate income tax, abolished the protective tariff, and broke up the 'credit trust'—a remarkable adumbration of Woodrow Wilson and his first term."[7] House's hero leads the democratic western United States in a civil war against the plutocratic East. After becoming the acclaimed leader of the country, he steps down having turned the US into “Socialism as dreamed of by Karl Marx”.[17] House outlined many additional political beliefs such as:[18]

· Federal Incorporation Act, with government and labor representation on the board of every corporation[18][19]

· Public service corporations must share their net earnings with government[18][19]

· Government ownership of all telegraphs[18][20]

· Government ownership of all telephones[18][20]

· Government representation in railroad management[18][20]

· Single term presidency[18][21]

· Old age pension law reform[18][22]

· Workmen's insurance law[18][22]

· Co-operative marketing and land banks[18][22]

· Free employment bureaus[18][22]

· 8 hour work day, six days a week[18][22]

· Labor not to be a commodity[18][22]

· Government arbitration of industrial disputes[18][22]

· Government ownership of all healthcare[18][22]

Our Introduction continues …

America has a Legacy of HOUSELESSNESS which has a long history dating back to the Civil War and Reconstruction period. Many national and state programs have been institutionalized from the 1850’s forward. This blog post presents the dates, names and descriptions of those programs. WHY?

1 - To demonstrate the exponential increase of HOUSELESS is not new to America;

2. - To illustrate that; despite repeated national and state: legislative, executive, and judicial attempts to erase HOMELESS from America’s Legacy, the “repeated” failures” of these attempts are self-evident; and

3. - A first step in any problem solving endeavor is admitting “there is a problem”!

“The word “hobo” first appeared in the 1880s in western America and softened the public's perceptions of tramps. This culture of migrant laborers was often romanticized in American literature, including by writers such as Walt Whitman, Bret Harte, and Sinclair Lewis. Jack London wrote vivid depictions of the “call of the road” as an escape from the oppression and monotony of factory work (Etulain, 1979). The storied hobo culture, popularized in the 1920s as “hobohemia” by Chicago sociologist and former tramp Nels Anderson (Anderson, 1923), faded as companies began to value loyalty and longevity and as seasonal jobs began to be taken by immigrant farm workers. …

When first used in the United States in the 1870s, the term “homelessness” was meant to describe itinerant “tramps” traversing the country in search of work. The primary emphasis at this time was on the loss of character and a perceived emerging moral crisis that threatened long-held ideas of home life, rather than on the lack of a permanent home. One religious group described the problem as “a crisis of men let loose from all the habits of domestic life, wandering without aim or home” (DePastino, 2003, p. 25). The solution to homelessness today is often perceived to be the creation or availability of affordable housing, but during the early 20th century, jobs (rather than housing) were viewed as the solution to the plight of transients wandering the country.”

The following 2 minute video sets the stage for the balance of this blog post and our focus of HOUSELESSNESS — as a continuing aspect of America’s Legacy.

This may be the first time readers learn about these chapters of history in our shared American Legacy. That is understandable. We now confront an exponential increase of HOUSELESSNESS today in 2025 — with many “root causes” being discussed by policy makers with differing agendas. Beyond the polemics, one uncomfortable fact is self-evident: HOUSELESSNESS in America is not new — it forms a well-documented Legacy in American history. An ADDITIONAL SHORT VIDEO HERE provides a second overview of our American Legacy.

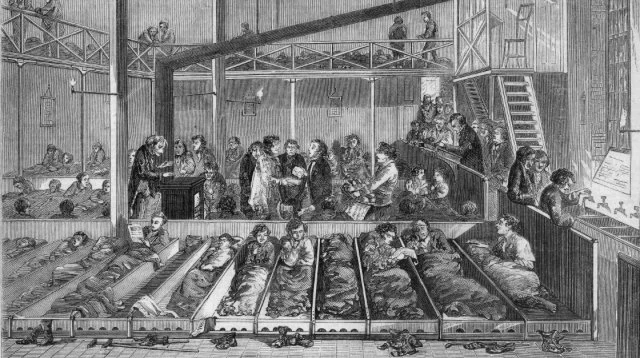

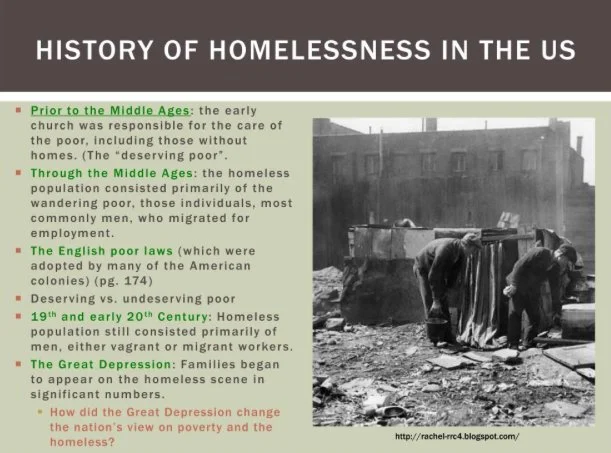

“During colonial times, early American attitudes toward poverty were shaped by English poor laws and the belief that some people were “worthy” of help while others were not. The original Elizabethan Poor Laws made it illegal to let anyone starve, requiring local communities to care for those in need. But by 1834, that system was replaced with the Poor Law Amendment Act, which only offered aid to the poorest men and women if they entered workhouses—harsh institutions where they were forced to perform exhausting and often degrading labor. These policies, and the values behind them, heavily influenced how early American settlers treated people experiencing poverty and homelessness. …”

The British Empire Debtor’s Prisons Policy | Impacts on IMMIGRATION to America | Continuance in the Colonies [PLEASE READ THE the document entitled: Appendix to a TEAM CONNECTED Blog Post (09.10.2055). On the subject of HOUSELESSNESS in colonial America:

“… Strict settlement laws controlled who was allowed to live in a community and who was forced to leave. These laws sorted people into different groups based on why they were poor, and treated them differently depending on whether their poverty was seen as “deserved” or “undeserved.”

The first documented cases of homelessness appear in colonial records from the 1640’s. European settlers were displacing Native Americans and resulting conflicts on the frontier also lead to homelessness among both Native Americans and Europeans. …”

“Homelessness dates back to 1640, according to Homelessness History. In the mid eighteen hundreds, homeless people were acknowledged as “sturdy beggars”. T he sturdy beggars were found in every corner of the colonial towns. Back then, Baltimore and Philadelphia had the highest population of homeless people. There was one big problem about homelessness at that time. It started the King Philip’ War of 1675 - 1676 against the native people. Many colonies were driven off their homes and ran to the forests for shelter. …”. SOURCE

“… In 1736, New York established its first almshouse. Poor houses and almshouses began opening across the colonies—many with rules and work requirements. During the Industrial Revolution and the transition to new manufacturing processes, there was mass movement to cities. This caused a new urban poverty that often resulted in homelessness, panhandling, and run-ins with the police.

Economic downturns in the 1830’s and 1850’s caused many to lose their jobs and homes. By the 1830’s, tens of thousands of homeless people lived in police stations by night and in the streets by day. I n the 1850’s, youth homelessness emerged when adolescent boys left home to look for work and ease the financial burden on their families. Many ended up homeless. …”

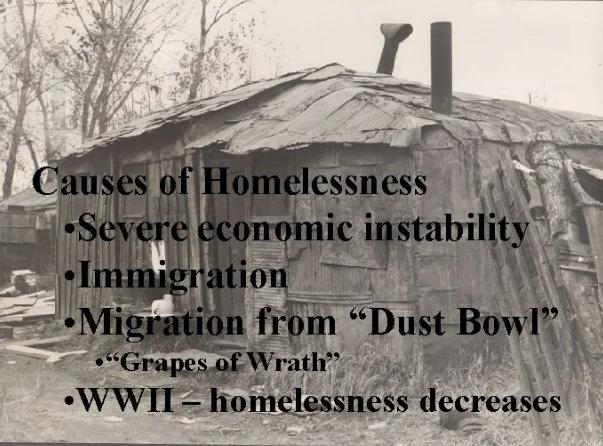

Post-Civil War America and the Great Depression were particularly harsh periods where homelessness surged due to economic downturns and a lack of adequate social safety nets.

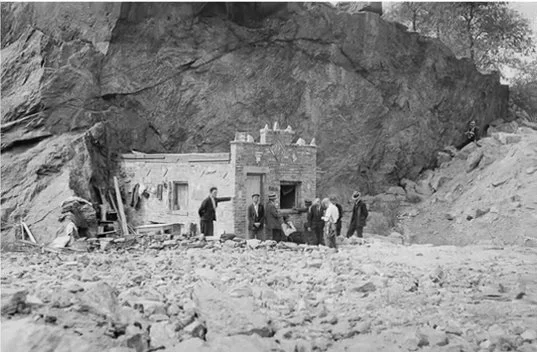

“… As people moved west during the Gold Rush and Civil War veterans traveled in search of new opportunities, expanded train routes made it easier to move from place to place. But with too few jobs to go around, many were forced to survive by seeking temporary work and scavenging for food and clothing. During this time, the terms “bum,” “tramp,” and “hobo” emerged to describe people experiencing homelessness—though the lifestyle was often romanticized in American literature. Homelessness wasn’t limited to major cities like Boston and New York; unhoused people were also found in small Midwestern towns and growing western cities like San Francisco.

From 1900 through the Great Depression, homelessness remained a widespread issue. Municipal lodging houses emerged during this time, highlighting the ongoing demand for shelter and basic services. The nature of homelessness also began to shift, as seasonal agricultural jobs that once offered temporary relief were increasingly filled by immigrant farm workers, leaving fewer opportunities for others. …”

Before the Great Depression, local philanthropic groups served meals, built shelters, and offered classes and job training. They often perpetuated the notion of “deserving” and “undeserving,” made judgments, and blamed people for their poverty. Faith-based organizations also began to open in poor parts of large cities. They provided shelter and a meal in exchange for a sermon and some hymns. During these years, tensions rose among the faith-based organizations, philanthropic groups, and publicly funded programs regarding the best way to address homelessness.

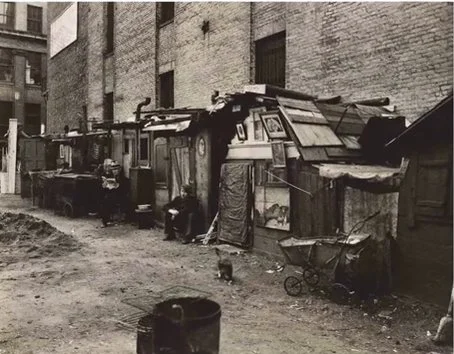

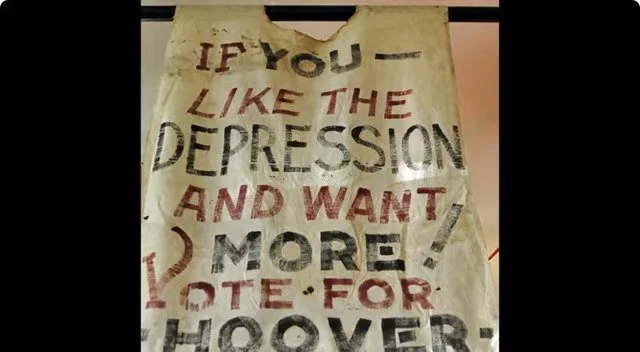

1930s Great Depression exacerbated these issues, resulting in widespread unemployment and displacement. During this time, makeshift encampments, known as ‘Hoovervilles,’ sprang up across cities as desperate families sought refuge. The government largely disregarded the plight of people experiencing homelessness, perpetuating a cycle of neglect that would last for decades.

In this short video about America’s Legacy of “Hoovervilles” during the Hoover administration, readers are encouraged to ask a simple question:

“Comparing America’s response to HOUSELESS people in the late 1920’s-30’s — is there similar language being used in 2025?”

National Responses to HOUSELESSNESS

Historians have extensively documented the prevalence of homelessness during the Great Depression. In response, President Franklin D. Roosevelt launched the first large-scale federal initiative to address the crisis: the Federal Transient Service (FTS). Before the FTS, aid for homeless individuals was handled locally, often inconsistently and inadequately. The FTS marked a radical shift in policy and a major milestone in the federal government’s role in homelessness. It provided shelter, job training, meals, medical and dental care, and even arts programs.

At its peak in 1934, the FTS served over 400,000 people annually. However, the program was never meant to be permanent—it was designed as a temporary measure to restore public confidence. By 1935, despite its success in reducing homelessness and helping people gain new skills, the FTS was dismantled. During this time, the face of homelessness remained largely white men, but many were now older, disabled, dependent on welfare, and living in single-room occupancy hotels (SROs) or cheap boarding houses in the poorest neighborhoods, including Skid Row districts.

As the Great Depression ended and World War II began, much of the country returned to work. However, homelessness did not disappear—it became increasingly concentrated in skid row areas of cities, where affordable housing, shelters, and social services were more readily available.

Summary of Appendix B | History of Homelessness in the United States

A Brief Timeline of HOUSELESSNESS [summarized from]: SOURCE

1820-30’s - The industrial revolution of the 1820s caused a large number of people to move to the Northeast, increasing the amount of people experiencing homelessness as they sought for work. In response, cities created laws that banned loitering and panhandling as well as begging in the streets. Furthermore, police departments would round up those who were homeless and put them in jails overnight. In 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, which was the first major federal legislation to create mass homelessness.

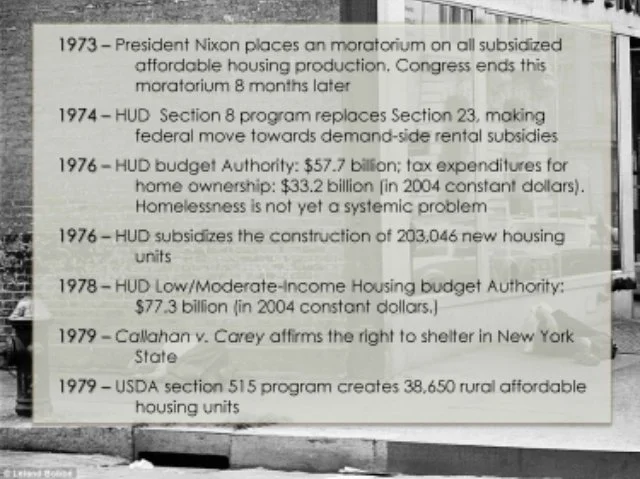

1892 - in 1892 Congress allocated $20,000 to the Department of Labor (DOL) to investigate urban slums in cities with at least 200,000 residents;

1932 - Emergency Relief and Construction Act of 1932 authorized the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to lend public funds to corporations to build housing for low-income families;

1933 - National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, which allowed the Public Works Administration (a government-sponsored work program) to use federal funds for slum clearance, the construction of low-cost housing, and subsistence homesteads; close to 40,000 housing units were produced that year;

1949 - In response to the severe housing shortage after the war, Congress passed the Housing Act of 1949. Its goal was to offer “a decent home and a suitable living environment for every American family”;

1965 - The Housing and Urban Renewal Act of 1965 (P.L. 89-117) was enacted as a rent supplement for low-income, disabled, and elderly individuals. Legislation in 1965 also formally created the Department of Housing and Urban Development. Finally, Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, the Fair Housing Act, established fair housing provisions to prohibit discrimination in access to housing;

1974 - The Housing and Community Development Act of 1974 (P.L. 97-35) merged several urban development programs into the broader Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program. This legislation also created the Housing Choice Voucher program, also known as the Section 8 program, to provide low-income housing through rental subsidies paid to the private sector. The “tenant-based” form of these rent subsidies, whereby families with a voucher choose and lease safe, decent, and affordable privately owned rental housing, is the mainstay of today's federal housing assistance programs for homeless and low-income individuals and families;

1984 - The Social Security Disability Benefits Reform Act of 1984;

1990 - Cranston-Gonzalez National Affordable Housing Act (P.L. 101-625)(1990);

The HUD Rule on Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing, authorized in 1968, was not published until 2016. Perhaps not surprising insofar as it took 50 years to issue the rule, enforcement of its provisions has been lackluster and inconsistent.

1977 - The first federal legislation enacted to explicitly address homelessness was the 1977 Stewart B. McKinney Homeless Assistance Act (PL 100-77). In addition to defining homelessness (see Box B-1), which is important for allocating federal resources, it also made provisions for using federal money to support shelters for persons experiencing homelessness. The McKinney Act also created a targeted Health Care for the Homeless (HCH) primary care funding stream, with a distinct broad definition of homelessness, which now exists within the Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) program.

1984 - The Social Security Disability Benefits Reform Act of 1984 was later enacted to pull back on some of the aspects of the 1980 Social Security Act, which impeded the efforts of some individuals experiencing illness and homelessness to pursue benefits.

1997 - The 1997 Stewart B. McKinney Act also authorized the creation of the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH). USICH is an independent executive branch body established to better coordinate homelessness programs across government agencies. The USICH includes representative membership from all major federal agencies whose mission touches upon homelessness, including, among others, HHS, HUD, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).1

2002-03 - In 2002, the USICH spearheaded the Chronic Homelessness Initiative, asking states and local jurisdictions to create 10-year plans to end chronic homelessness. Another change in federal policy occurred in 2003, bringing a focus on “ending chronic homelessness” through low-threshold and permanent supportive housing programs (HUD, 2007a). At that time, through a collaborative process overseen by the USICH, the federal government formally defined chronic homelessness as “an unaccompanied homeless individual with a disabling condition who has either been continuously homeless for a year or more or has had at least four episodes of homelessness in the past three years” (HUD, 2007a, p. 3)

2009 - The next reauthorization of the McKinney-Vento Act, called the HEARTH Act, was signed into law in 2009. The reauthorization consolidated several existing programs for individuals experiencing homelessness, created a federal goal that individuals and families experiencing homelessness be permanently housed within 30 days, and codified the planning processes used by communities to organize into Continuums of Care in order to apply for homeless assistance funding through HUD.2 New definitions of “homeless,” “homeless person,” and “homeless individual” were expanded. These changes were based on Congress identifying (1) a lack of affordable housing and limited housing assistance programs, and (2) an assertion that homelessness is an issue that affects every community.

2010 - In 2010, under President Obama's administration, a federal strategic plan to end homelessness was released (USICH, 2017). The federal strategic plan established four key goals: (1) Prevent and end homelessness among Veterans in 5 years; (2) Finish the job of ending chronic homelessness in 7 years; (3) Prevent and end homelessness for families, youth, and children in 10 years; and (4) Set a path to ending all types of homelessness.

2001-2010 - “… During the 2000s, the number of homeless people continued to increase. The U.S. continues to experience an affordable housing crisis. This is due to the high cost of housing, lack of affordable housing stock, and wages that have not kept up with the cost of housing.

Many states—encouraged by the federal government — began developing and implementing plans to end homelessness during the 2000s. Prior to this, the dominant approach was the Staircase Model, which required individuals to meet certain goals—such as sobriety or employment—before progressing to independent housing. In the 1990s, officials introduced the Housing First model, which reversed this approach by providing housing without preconditions.

Backed by growing research throughout the 2000s, Housing First gained momentum for its effectiveness in helping certain populations, especially those with chronic health or behavioral health challenges. Another emerging model, the Vulnerability Index, prioritized people who had been homeless for at least six months and had one or more serious health conditions for access to housing.

During the Great Recession of 2007-2009, many people defaulted on their mortgages due to economic conditions and the real estate market. As a result, there was a big increase in foreclosures, evictions, and unemployment, which led to increased homelessness.

In 2010, the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness developed Opening Doors, a strategic federal plan to end homelessness.

2010-18 - Officials updated the plan in 2012, 2015, and 2018, leading to measurable progress, particularly in reducing veteran homelessness. However, in recent years, progress has slowed. …”. SOURCE

REFERENCES

• Anderson N. The Hobo: the Sociology of the Homeless Man. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1923.

• Bostic RW, Thornton RLJ, Rudd EC, Sternthal MJ. Health in all policies: the role of the US Department of housing and urban development and present and future challenges. Health Affairs. 2012;31(9):2130–2137. [PubMed]

• Collin RW, Barry DJ. Homelessness: A post-industrial society faces a legislative dilemma. Akron Law Review. 1987;20(3):409–432.

• Congressional Budget Office. Federal Housing Assistance for Low-Income Households.2015. [August 6, 2017]. https://www .cbo.gov/publication/50782.

• Congressional Research Service. A Chronology of Housing legislation and Selected Executive Actions, 1892-2003. 2004. [September 29, 2017]. https: //financialservices .house.gov/media/pdf/108-d.pdf.

• Culhane DP, Gollub E, Kuhn R, Shpaner M. The Co-Occurrence of AIDS and Homelessness: Results from the Integration of Administrative Databases for AIDS Surveillance and Public Shelter Utilisation in Philadelphia. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2001;55:515–520. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

• Culhane DP, Metraux S, Park JM, Schretzman M, Valente J. Testing a Typology of Family Homelessness Based on Patterns of Public Shelter Utilization in Four U.S. Jurisdictions: Implications for Policy and Program Planning. Housing Policy Debate. 2007;18(1):1–28.

• Culhane DP, Khun R. Patterns and Determinants of Public Shelter Utilization Among Homeless Adults in New York City and Philadelphia. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 1998;17(1):23–43.

• DePastino T. Citizen Hobo: How a Century of Homelessness Shaped America. Chicago Scholarship Online. 2013. [September 29, 2017]. [CrossRef]

• Desmond M. Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City. New York, NY: Crown; 2016.

• Eisenstein M. Disease: Poverty and Pathogens. Nature. 2016;531:S61–S63. [PubMed]

• Etulain RW. Jack London on the Road: The Tramp Diary and Other Hobo Writings.Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press; 1979. pp. 41–54.

• Flynn K. The Toll of Deinstitutionalization. In: Brickner PW, Sharer LK, Conanan B, Elvy A, Savarese M, editors. The Health Care of Homeless People. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 1985. pp. 189–190.

• GAO (U.S. General Accounting Office). Report to the Subcommittee on VA, HUD and Independent Agencies. Committee on Appropriations, House of Representatives. Housing for Persons with AIDS. Washington, DC: GAO; 1997. GAO/RCED97-62.

• HUD (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development). Defining Chronic Homelessness: A Technical Guide for HUD Programs. 2007a. [September 29, 2017]. https://www .hudexchange .info/resources/documents /DefiningChronicHomeless.pdf.

• HUD. Programs Administered by the Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity (FHEO).2007b. [September 29, 2017]. https://portal .hud.gov /hudportal/HUD?src= /program_offices/fair _housing_equal_opp/progdesc/title8.

• HUD. Major Legislation on Housing and Urban Development enacted Since 1932. 2014. [September 29, 2017]. https://portal .hud.gov /hudportal/documents /huddoc?id=LEGS_CHRON_JUNE_2014.doc.

• Jones MM. Creating a Science of Homelessness During the Reagan Era. Milbank Quarterly. 2015;93(1):139–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

• Katz B. Racial Division and Concentrated Poverty in U.S. Cities. Urban Age Conference; Johannesburg, South Africa. 2006. [September 29, 2017]. https://www .brookings .edu/wp-content/uploads /2016/06/20060707_UrbanAge.pdf.

• Kim S, Margo RA. Historical Perspective on U.S. Economic Geography. 2003. [September 29, 2017]. http://www .econ.brown .edu/Faculty/henderson/kim-margo.pdf.

• Kusmer KL. Down and Out, On the Road: The Homeless in American History. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2002.

• Lebow JM, O'Connell JJ, Oddelifson S, Gallagher KM, Seage GR III, Freedberg KA. AIDS among the homeless of Boston: a cohort study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes and Human Retrovirology. 1995;8:292–296. [PubMed]

• Lipsitz G. Government Policies and Practices that Increase Discrimination. 2008. [September 29, 2017]. http://www .prrac.org /projects/fair_housing_commission /chicago/lipsitz.pdf.

• McCarty D, Argeriou M, Huebner RB, Lubran B. Alcoholism, Drug Abuse, and the Homeless. American Psychologist. 1991;46(11):1139–1148. [PubMed]

• Neiderud CJ. How urbanization affects the epidemiology of emerging infectious diseases. Infection Ecology and Epidemiology. 2015;5(10.3402/iee.v5.27060) [PMC free article] [PubMed]

• Rossi PH. Down and Out in America: The Origins of Homelessness. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press; 1989.

• Rossi PH. The old homeless and the new homelessness in historical perspective. American Psychologist. 1990;45(8):954–959. [PubMed]

• USICH (U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness). United States Interagency Council on Homelessness Historical Overview. 2016. [September 29, 2017]. https://www .usich.gov /resources/uploads/asset_library /USICH_History_2016.pdf.

• USICH. Opening Doors. 2017. [May 8, 2018]. https://www .usich.gov/opening-doors.

• Wayland F. Papers on Out-Door Relief and Tramps, Read at the Saratoga Meeting of the American Social Science Association, before the Conference of State Charities. 1877. [June 8, 2017]. http://quod .lib.umich .edu/m/moa/aaw7999.0001 .001/10?view=text.

. http://quod .lib.umich .edu/m/moa/aaw7999.0001 .001/10?view=text.